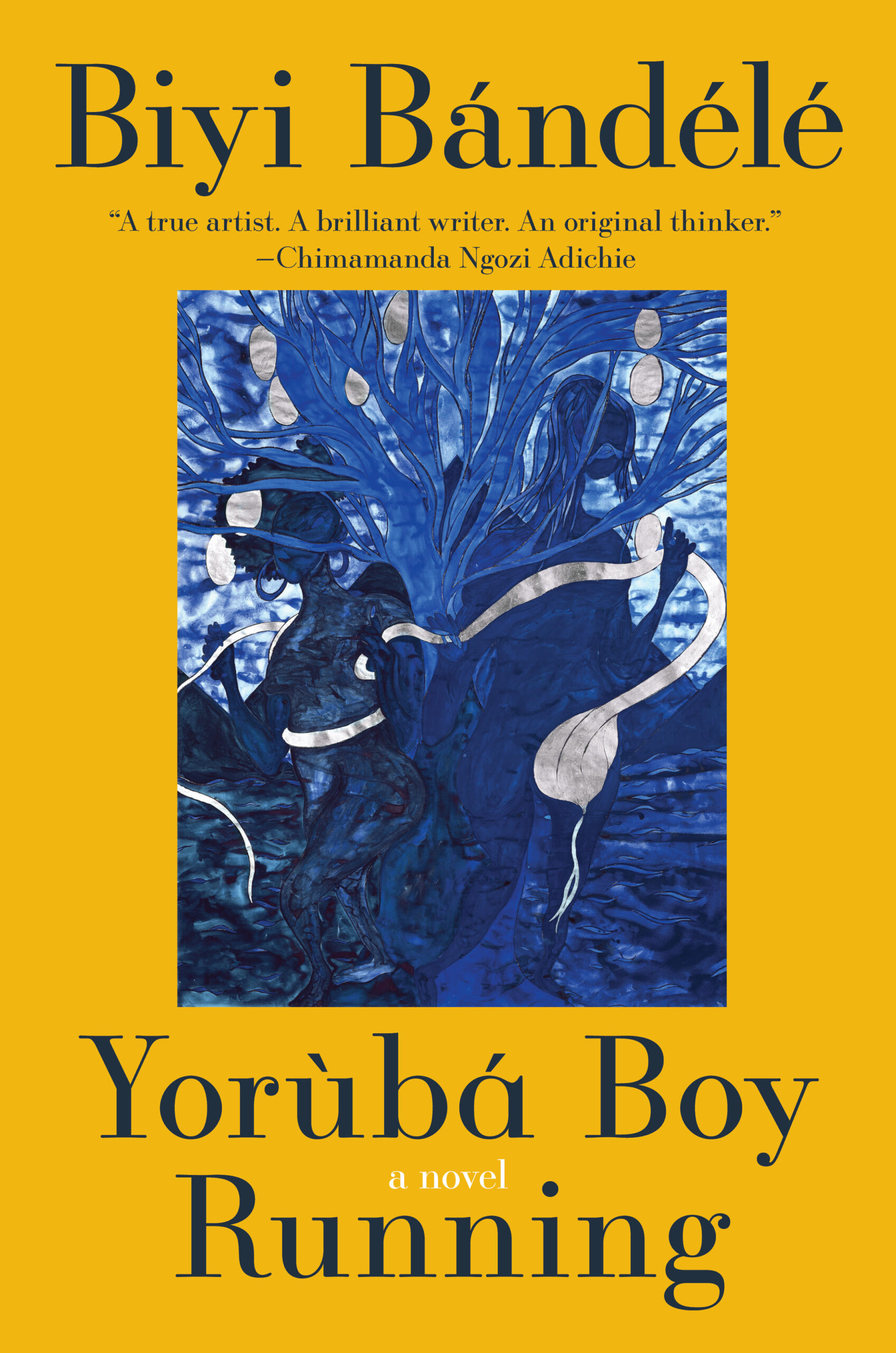

The following is from Biyi Bandele’s Yoruba Boy Running. Bandele (1967–2022) was a pioneering novelist, playwright and film-maker. Born in Northern Nigeria to a veteran of the Burma campaign, winning a British theatre award brought him to London at age 22, where he published his first two novels and went onto write and direct many acclaimed plays, novels and feature films in the UK and Nigeria. The Independent named him one of Africa’s Fifty Greatest Artists.

On the night before the Malian swordsmen swept into Òṣogùn, chanting, ‘God is great, God is great, God is great,’ as they laid waste to the town and corralled its inhabitants into barracoons, all twelve thousand of them, and herded them down to a mosquito-infested backwater on the coast, an obscure fishing village christened Lagos by the Portuguese merchants whose trade in human cargo had brought them there, Àjàyí had a dream in which he saw the god Ọ̀ sanyìn hunched over, his notched and scarified, weather-beaten face drawn and dejected, gathering herbs in the dank forests sprawling beyond the six gates of the town’s encircling walls.

Article continues after advertisement

In Àjàyí’s dream, the healer god was blind in one eye, and had just one leg and but one arm. The god’s left ear was big as a cassava leaf, but he was deaf in this ear. If he was deaf in his left ear, which wasn’t quite as big as a cassava leaf, truth be told, spare a thought for his right ear, which was no ear at all. It was a dimple. Where others would seek out their right ear, Ọ̀ sanyìn had a dimple. Where some had a dimple, Ọ̀ sanyìn had his right ear. Needless to say, he was deaf in this ear too. And yet all he had to do was cup the dimple with the mud-encrusted fingers of his stubby hand and he could hear a moth on the wing.

In place of hair, a wild constellation of tousled beads on the òrìṣà’s misshapen head shone like night light from a distant place. Beads of every hue sparkled on his head, and each time he plucked a healing herb on the forest floor it was as if he were harvesting the very beads on his head.

When Àjàyí arose from his mat the next morning, he knew exactly what to do about the dream. He would ask Ìyá what it meant. It was the only thing to do. There was certainly no point asking his sister, Bọ́lá. Bọ́lá would simply stare him down and say, ‘Go away, child,’ without actually saying ‘child’ or even ‘go away’. She would simply stare him down.

There was a time when he could count on Bọ́lá as an ally, a partner-in-crime. But those days were long gone. Any such understanding between them ended the day Àkànní the hunter came asking for her hand. Since the day she became betrothed to the most revered elephant hunter in the land, Bọ́lá had taken to treating everybody – namely, the boys – like something Àkànní’s dog Konginikókó dragged in from a hunt. It was not so much that Àjàyí faulted Bọ́lá’s choice of husband. What was hard to stomach was that his own sister would choose to treat him, her flesh and blood, like a wastrel and a fool.

Better to ask Ìyá, he decided. Ìyá knows best.

In the unlikely event Ìyá didn’t know, she would bring the matter to the attention of Ìyálóde. She would go to Ìyálóde ’s shrine and ask her. Ìyálóde was the òrìṣà of purity. There was hardly a question on the Maker’s earth that Ìyálóde could not answer. She was, after all, the First Lady of the Universe.

Ìyálóde knew all there was to know about the land of the living, which is everything under the sun, and beneath the sea, and in the realm of the stars. And she knew all there was to know about the land of the ancestors, where all must go who depart the land of the living, as all mortals must do to reach immortality. And she knew all there was to know about the land of the unborn, the womb of all wombs through which the ancestors, deathless all of them, must navigate their way to the land of the living, where they occasionally must go because even immortals sometimes need a break.

*

With the dream of the òrìṣà vivid in his mind, Àjàyí sprang up from his mat and headed to his mother’s hut.

He stretched out flat on his face and bid Ìyá good morning. He would have gone to his father’s workshop and done the same thing, but Bàbá had left home well before cockcrow that morning to tap his palm trees.

As he lay at Ìyá’s feet, flat on his chest on the earthen floor, Àjàyí quickly sensed that his mother was in no mood to hear about his dream. Only the week before, he had told her about a dream in which the goddess Ọya had appeared to him with tears streaming down her face. ‘I’ll make tears stream down your face,’ Ìyá had responded, ‘if you don’t go and fetch water for your father’s morning meal.’

He knew he wouldn’t fare any better today, but there was no harm in trying. As he opened his mouth to speak, Bọ́lá, who was running a comb through the dense thicket of Ìyá’s shimmering black hair and palming òrí into it, took one look at him through the corner of her eyes and stopped him dead in his tracks.

‘Mother,’ she said, without once taking her eyes off Ìyá’s head, ‘your son has had another one of his dreams. I can see it clearly in his eyes’ – she said this without even looking at him. ‘He looks like a haunted rat. He always looks like a rat when he’s had one of those dreams.’

Àjàyí swallowed hard, doing his best not to cast a spiteful look her way.

‘If you do that again—’ Bọ́lá warned him, even though Ṣàngó knew, and Ògún knew, and all the òrìṣà knew, that he’d done no such thing.

He’d had enough of her for one morning.

‘I don’t look like a haunted rat,’ he muttered as he turned to leave, his eyes clouding with tears.

‘Forgive me,’ said Bọ́lá. ‘You’re right. You don’t look like a haunted rat.’ She waited until he was by the door, before adding, ‘But you do bear more than a passing resemblance to the grasscutter Lánre caught in the palm grove last night. Are you by any chance related?’

‘Tell her to stop calling me a rat, Mother!’

‘How dare you call my bàbá a rat, Bọ́lá’ – Ìyá called him her father because Àjàyí was the spitting image of his grandbàbá. ‘How dare you. My bàbá is a prince, not a rat.’ Her eyes were twinkling with laughter. ‘Come here, my father,’ she said. ‘Don’t mind your sister. Blame it on ojú kòkòrò.’ Envy, sheer envy. ‘I’m all ears. Tell me about your dream. Tell me all about it. Spare no details.’

And so, sitting at her feet, he told his mother about his dream of the healer god who looked sorely in need of healing and about his missing leg and his sawn-off arm and his sightless eye and his deaf ears and his hearing dimple and his many-coloured beads and his speckled herbs and, most of all, about the depthless sadness in the god’s lonesome eyes.

Ìyá listened with rapt attention. Bọ́lá did, too, until he mentioned the dimple. The dimple. Did he actually say dimple?

‘Did you actually say dimple?’ she asked him.

When he mentioned the dimple, Bọ́lá’s eyes narrowed down to a squint, the better to contemplate his lips, which were surely not lying.

‘We have heard of white men who turned the ocean into a highway,’ she gravely declared. ‘But did you just say the òrìṣà could hear with his dimple? Is that what you said?’ And now she bent over and began to make a strange sound, the sound of throttled laughter. ‘Did your son actually say that,’ she asked Ìyá, ‘or have I lost my dimples and gone deaf?’ And now she held her sides and shook, the tears streaming down her cheeks.

Ìyá patiently waited for her to finish laughing. ‘Have you finished laughing?’

‘But I’m not laughing, Mother.’

She waited until Bọ́lá had stopped laughing before turning, once again, to Àjàyí. ‘You saw Ọ̀ sanyìn.’

‘Yes, Mother,’ Àjàyí replied.

‘Ọ̀ sanyìn, the gods’ own sorcerer.’ ‘Yes, Mother.’

‘Ọ̀ sanyìn, the òrìṣà of health and well-being.’ ‘Yes, Mother.’

‘And he looked unwell.’ ‘He looked as if he had ibà.’

Bọ́lá’s eyes widened in disbelief. ‘The òrìṣà Ọ̀ sanyìn has ibà?’ Ibà, the fever malaria.

‘I didn’t say he had ibà,’ retorted Àjàyí. ‘I said he looked like he had ibà.’ He addressed this information to Ìyá, even though it was Bọ́lá who had asked him the question.

‘Was Ọ̀ sanyìn pouring with sweat?’ Ìyá asked. ‘He was drenched in sweat, Ìyá.’

‘That’s a dead giveaway. He must have ibà.’ Àjàyí tapped Bọ́lá on the shoulder.

‘Did you hear that? Ìyá thinks I’m right.’

‘If you come anywhere near me again,’ Bọ́lá said threateningly, speaking to the hand Àjàyí used to tap her on the shoulder as if the hand was a being separate from and independent of its owner. The hand beat a hasty retreat.

Àjàyí nodded in eager agreement to something their mother had said while his sister was threatening his hand.

‘And he looked haggard and unhappy,’ she had said. ‘Yes, Ìyá,’ he replied. ‘He looked unhappy.’

Bọ́lá’s sceptical eyes measured him from head to toe.

‘Mother,’ she pleaded. ‘I must ask you at once to stop indulging this child. How could you tell it was the òrìṣà himself?’

‘It was him,’ Àjàyí insisted, his voice rising.

‘You keep saying that,’ said Bọ́lá, ‘it’s your word against Ọ̀ sanyìn’s dimple,’ and that set her off again.

‘Don’t you mind her, Àjàyí,’ Ìyá told him. ‘Don’t mind her at all.

Did the òrìṣà speak to you?’

The blank stare in Àjàyí’s eyes was all the answer Bọ́lá needed. ‘Of course the òrìṣà didn’t speak to him,’ she sniggered. ‘They

never speak to him. They keep turning up in his dreams. And then they don’t say a word. They ignore him.’

Ìyá ignored her.

‘Did the Lord of the Leaves speak to you, Àjàyí?’ Àjàyí shook his head. ‘No.’

‘Not a word?’ ‘Not a word, Ìyá.’

‘But he looked unhappy.’

‘He looked unhappy,’ Àjàyí said, looking unhappy, and wishing he’d had the presence of mind to ask the òrìṣà why he looked so unhappy.

Bọ́lá, who had a knack for reading his mind with unerring precision, now read his mind.

‘It’s no use being sad,’ she told him. ‘Next time you fall asleep and find yourself in the presence of an òrìṣà, open your mouth. Talk to them. They won’t bite you. They might even talk to you.’

Àjàyí fixed his eyes on Ìyá and tried to pretend Bọ́lá didn’t exist.

He clenched his lips firmly so that all the rich insults he so badly wanted to rain on her dried up in his throat.

__________________________________

From Yoruba Boy Running by Biyi Bandele. Copyright © 2024 by the Estate of Biyi Bándélé. Reprinted here with permission from Harper, an imprint of HarperCollins Publishers.