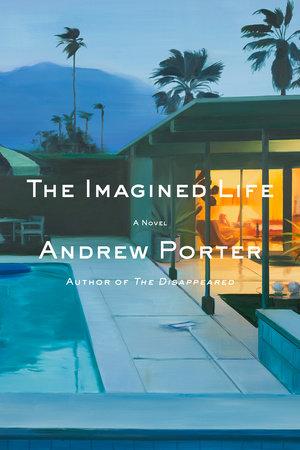

The following is from Andrew Porter’s The Imagined Life. Porter is the author of the story collection The Theory of Light and Matter and the novel In Between Days. A graduate of the Iowa Writers’ Workshop, he has received a Pushcart Prize, a James Michener/Copernicus Fellowship, and the Flannery O’Connor Award for Short Fiction. His work has appeared in One Story, The Threepenny Review, and Ploughshares, and on public radio’s Selected Shorts. Currently, he teaches fiction writing and directs the creative writing program at Trinity University in San Antonio, Texas.

At the beginning of August that summer—that summer I was eleven—I remember there being a series of very hot days, a kind of minor heat wave, including one day when the temperatures topped off in the triple digits, the heat refusing to burn off, even at night. We didn’t have air-conditioning at the time—you rarely needed it in southern California—but I remember one day my father went out and came back with a trunk full of electric fans of various sizes and shapes. Large box fans, small oscillating fans, fans that you could adjust to different angles and heights. Standing at the kitchen sink, my mother and I watched him through the kitchen window as he carried several of these fans into the cabana house, where he was still living, and others into the main house, placing one in almost every room. I could tell from my mother’s expression that this was an expense we couldn’t afford, an impulsive extravagance, but she didn’t say a word. She just thinned her lips and ran her hand along the edge of the counter, searching for her cigarettes, her eyes still set on my father.

Article continues after advertisement

Later that day, she took Chau and me to the movies, a momentary respite from the heat, and when we returned I remember finding my father floating on a raft in the middle of the pool, a cold can of Miller Lite balanced on his flat stomach, his eyes obscured behind his Ray-Bans. My mother shepherded Chau and me into the kitchen, as if wanting to protect us from seeing something, then went back out to the pool to talk to him, squatting down beside the edge and saying something to him as he continued to float there, motionless, obviously discouraged and disheartened.

Earlier that day, before he’d gone out to buy the fans, I’d overheard him talking to my mother about the fact that the university press that had promised to publish his first book was now beginning to get cold feet, or at least it seemed that way to him. The two of them were sitting in the kitchen, and I was lying in my bed down the hall, but I could hear the desperate lilt of my father’s voice and could tell that this was serious. They were demanding rewrites, he said, when before they’d said everything looked fine. They also claimed that one of the reports from an outside reader, an anonymous professor at another university, had recommended against publication, so they would need to approach a third reader. For some reason, this last fact seemed to trouble my father the most. He seemed incredulous that someone could recommend against publication given the fact that most of the individual chapters in his book had already been published as separate articles in top journals in his field. I didn’t know what any of this meant at the time, but I did understand the significance of this book, how it represented a kind of protective shield against the people my father believed were conspiring against him in his department. As long as he had this book, he believed, they couldn’t touch him. They couldn’t deny him tenure.

Later, he’d begun to speculate about why this might be happening and who might be trying to sabotage him. Had someone from his department called the editor at the press? Had David Havelin leaked it? Eventually, frustrated by the heat, he’d gone out to buy the fans, claiming that he’d just need to work harder now, though it was clear the fans hadn’t helped, that a part of him had given in to the sweltering heat, the innumerable forces working against him. Chau and I watched my parents for a bit and then headed down the hallway to my room. I could tell that Chau was disappointed by the fact that we wouldn’t be able to use the pool now, something that I’d promised him on the way home. Instead, we sat on the floor of my bedroom, both of us sweating in front of the small fan that my father had brought in earlier that day, listening to “Crazy on You” by Heart and then later to the tape of Rumours that Deryck Evanson had given me. I had managed to convert Chau into a Fleetwood Mac fan too, though he wasn’t as fanatical about Stevie Nicks as I was. He told me that he thought she was a little “witchy” and that his older sister had told him that she might actually be one. That day, though, we both sat hypnotized by her voice in the still heat of my bedroom, the hazy afternoon sunlight making us drowsy, saturating the room with warmth.

At one point Chau stood up and suggested we cool off in the shower down the hall. It wouldn’t be as good as the pool, he said, but at least it would be better than this. We could wear our bathing suits, he said, turn the shower valve all the way to the coldest setting.

I was hesitant at first but eventually I stood up and followed him down the hallway to the bathroom. Once inside, he peeled off his T-shirt and then locked the door behind us. I watched him turn the water to the coldest setting then kick off his flip-flops. He was wearing a pair of Ocean Pacific surfer shorts, like me, and after a moment he stepped into the shower and let out a loud yelp, too cold, too cold, he shouted, and then he danced around a bit, as he adjusted the valve to the right level of coldness. Come on, he said, reaching out and grabbing my arm, pulling me into the narrow tub, the cool water like a shock to my skin, but a pleasant one, and then both of us laughing, jockeying for position, slipping on the slick surface of the tub, almost falling out, and then laughing again. And I have to admit, it felt good, better than good, the cold water on my skin, Chau’s arms wrapped around my chest, both of us laughing, a kind of horseplay, and then later, working up a lather with the bar of Zest, placing the suds on each other’s chins, making soapy beards, mustaches, talking like Obi-Wan Kenobi, Use The Force, Luke, then rinsing ourselves off and doing it again. At several points I remember feeling relieved that my parents weren’t inside and that Chau had locked the door, though I couldn’t say why, only that it somehow felt like something they shouldn’t see or know about, and later, as we lay on the floor of my bedroom, both of us still wet from the shower, I remembered the way that Chau’s hand had brushed against the front of my bathing suit several times and the jolt it had given me, the way I’d enjoyed it.

Now, lying supine on our backs, the late afternoon sunlight beginning to fade, the room growing darker, I felt an awkwardness settling in, forming between us, a mutual embarrassment about what had happened in the shower perhaps, but also, strangely, a closeness. I reached over and turned down the volume on the stereo, and when I looked back at Chau his eyes were closed. I lay back down next to him and closed my eyes as well. I thought about my father and Deryck Evanson dancing with those men on the flagstone patio deck and suddenly felt ashamed. Then I felt myself beginning to relax, my limbs growing heavy, drifting off slowly into sleep.

*

When I woke up several hours later, the room was dark and Chau was gone. I lay there for a while on the floor, trying to process where I was. It was still hot, the air thick with it, and I could feel a dampness in my hair at the back of my head. After a while, I wandered down the hallway to the kitchen to make myself some dinner. Earlier that day, my mother had stocked up the pantry with cereal, so I stood at the counter next to the sink, eating a bowl of Cap’n Crunch in the dark and watching my parents through the kitchen window, as they sat in lawn chairs down by the pool, watching a black-and-white movie that my father had projected up onto the side of the cabana house. The volume on the projector was low, too low to hear very much, but I could still tell from the visuals, from the close-ups of Ingrid Bergman and Cary Grant, that it was Alfred Hitchcock’s Notorious, a favorite of my father’s and a film that I’d watched with my parents several times before.

In earlier days, I would have probably gone down and joined them, snuggled in between them, but I was so pleased by the sight of them sitting together, my mother’s head resting on my father’s shoulder, their bodies pressed together, that I just stood there, watching them, not wanting to disturb them or jinx what was happening.

At one point, my father stood up to get them some more beers from the cabana house, and when he returned he leaned down slowly and kissed my mother on the lips, a soft, gentle kiss, placing the bottles down on the grass beside them, then cupping her face in his hands. Even now, years later, I can still picture that moment, the two of them frozen in silhouette, the bright silver light from the screen, my mother’s hand reaching up and gripping my father’s shoulder tightly, the images of Cary Grant and Ingrid Bergman hovering above.

*

Later that night, they’d ended up stumbling into the house drunkenly, knocking over a table lamp in the kitchen as they made their way clumsily toward their bedroom, laughing and shushing each other, telling the other to be quiet, that they didn’t want to wake me, but then giggling again, finally finding the door to their room and pushing through.

In my younger years, I used to find moments like this frightening, moments when my parents seemed out of control, but that night it filled me with a strange warmth, a comfort. The knowledge that they were sleeping in the same bed together again, that Deryck Evanson was nowhere in sight. It was one of the last moments I could remember feeling hopeful about their marriage.

*

The next morning my father would wake and begin working feverishly on a new project, a new book proposal that he planned to submit to a new press. He’d be in a panic, the beginning of a lengthy manic phase, one that would last for several days, but for that evening, at least, he seemed back to his old self. Not depressed, but not manic-y either. My mother had managed to calm him down and reel him back in (a couple of beers and a film noir, that was it), and now I could hear them through the walls of my room, giggling like teenagers. My father saying something theatrical, my mother trying not to laugh, but ultimately losing it, falling into convulsions. The two of them rolling around on top of the sheets, knocking things over. That mirth. It wasn’t always there, but when it was it was palpable. Contagious. And I remember lying there in my bed, not bothered by the noise at all, but actually enjoying it, wanting to fall into it, the way one wants to fall into a memory or a dream or a song, the way you want to believe this momentary feeling is a deeper truth, a path that you can choose, rather than a fleeting kind of bliss, a film that might end.

After a while, the laughter died down, and the hall became silent, the only sound coming from the numerous fans whirring in the distance, in every room in the house, a kind of mesmerizing hum, like the voices of a chorus or the communal buzz of a swarm.

I got up after a while and walked down the hallway to their room. I stood outside their door and listened—listening for what, I’m not sure, only that I know it made me happy to be there, standing in the darkness outside their room, listening for their voices, their laughter, any sign that they were still in there and that life as I’d once known it might one day return to normal.

__________________________________

From The Imagined Life by Andrew Porter. Copyright © 2025 by Andrew Porter. Excerpted by permission of Alfred A. Knopf, a division of Penguin Random House LLC. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.

Audio excerpted with permission of Penguin Random House Audio from THE IMAGINED LIFE by Andrew Porter, read by Lee Osorio. © Andrew Porter ℗ 2025 Penguin Random House, LLC.