When I first came to the United States, I was surprised by how much I missed the atmospheric soup that is New Delhi. It’s the unapologetic buzz of a multilingual city and its daily life—the latest Hindi, English, and Punjabi songs crooning from neighboring homes and shops; bells and calls for prayers from temples and mosques; and conversations in languages as disparate as Urdu, Tamil, and Bengali.

Article continues after advertisement

I decided that the only way I could hold on to everything in New Delhi was by keeping an eye out for every movie, song, or even advertisement made in the language I missed the most, Hindi. I was going to watch it all, so that when I returned, whether after a year or three, I would slide right back to where things were when I left. No one, friends or family, would be able to tell that I was ever gone from the country.

Through the entirety of that first semester, on afternoons when I didn’t have classes or homework, I would check out a laptop from the campus library, plug in my headphones, and search for every Hindi song and movie just released in India. This was how I was going to hold on with all my might, resisting and defying the forces of change.

*

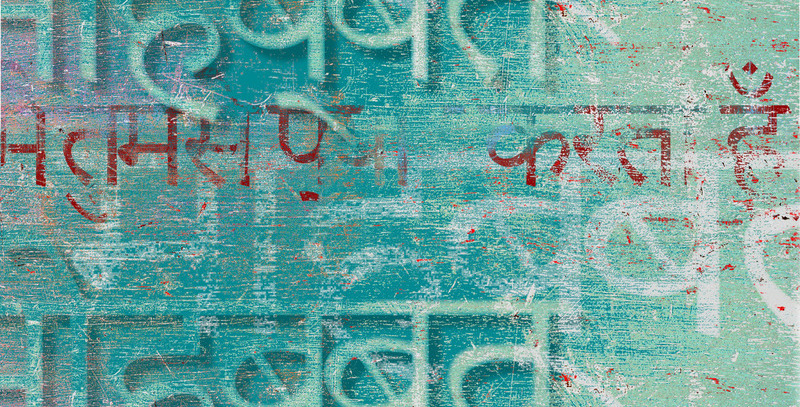

Hindi entered my life when I was five years old and my parents and I moved from Kolkata to New Delhi. At home we still spoke Bengali, but since Hindi was the primary language of our new city, I was now required to learn it quickly. Bengali and Hindi are both derived from Sanskrit, so one might think that if you already know one, you might pick up the other with ease, especially since they share a few identical-looking letters. But that is not the case. Sure, the two languages have a few words in common, but for the most part, they sound different, and they have their own unique grammar and script.

This was how I was going to hold on with all my might, resisting and defying the forces of change.

For one, Bengali has no gender. Everyone can be described using the same pronouns, whether one’s father or mother, teachers, the Catholic nuns at school, or, say, the neighbors who forgot to get you a gift on your last birthday. In Hindi, on the other hand, everything has gender, including, most mystifyingly, buses (feminine) and trucks (masculine).

Bengali contains twenty-eight letters, and Hindi forty-four. I am just starting to figure out these shapes when English is also introduced in my life, shoving twenty-six additional letters into my orbit. Now, there’s five-year-old me, and ninety-eight letters I must be able to read and write.

At least they are all written from left to right, so that’s one less thing to be confused about.

A few years later, when I am ten, I learn that Bengali and Hindi are the fifth and sixth most spoken languages in the world. I am blown away by this fact. It’s funny to me that millions and millions of people in the world apparently say or write the same things as I do. Then who am I? Am I really me, or an echo of all these others?

*

When I talk to my mother on the phone, my husband insists it sounds like “Haashe paashe haashe paashe khororororo.” It makes me giggle, this imitation, this string of nonsense words. Bengali is not one of his languages, but now, after fifteen years together, he has mastered the important stuff. He knows how to swear in Bengali, and how to say, “I am hungry,” “This is delicious,” and “I must use the bathroom.”

My husband speaks to his mother in Punjabi, a language I understand but cannot speak. He usually emerges from these conversations relaxed and smiling. He laughs and exchanges gossip with her, begs for recipes that he loved as a kid and wants to re-create in our kitchen. He teases her when her measurements are vague, when she issues instructions like, “Oh, just throw in a pinch.” A day or so later, when he updates her on how the food turned out, it’s like I have a window into his childhood. Look, here he is, talking to his first friend, his source for his mother tongue.

*

As someone born in a former colony of Britain, my fluency and, dare I say, expertise in English is neither unusual nor unique. There are many others like me. It makes me wonder if I would have felt the same longing for, say, French, Dutch, or Portuguese if India had been thoroughly and absolutely colonized by one of those countries instead. (I wonder about this because it’s not as if they didn’t try; they just didn’t succeed.)

In A Thousand Years of Good Prayers, Yiyun Li writes, “English is my private language.” When I was growing up, English didn’t feel “private” to me, perhaps because I was surrounded by English speakers both in my family and outside. Neither does it feel “private” now when I am surrounded by English speakers every second of my life, including at home, where I speak English with my husband, and at the university, where I teach creative writing.

But yes, the inherent logic of English has always come easily to me. It has given me a sense of ownership that I haven’t felt over my other languages.

As a child, I read extensively in Bengali, Hindi, and English. I wrote stories and poems in Hindi and English, the languages I got to practice daily in school.

But somewhere along the way, things changed.

English and Hindi entered a boxing ring. They put on gloves and faced each other. There was no point, though. I already knew the outcome. The game was rigged from the start. Hindi was going to lose, and this is because when I was growing up, the Hindi literature curriculum at school often felt old and cobwebby. There were poems and stories about patriotism and pious gods set in hinterlands, far from any place I knew.

On those cruelly hot afternoons, inside classrooms that contained no more than three overhead fans for fifty-plus students, how could I be expected to care for events that had transpired during my grandparents’ time or long before? If only I had read a story or two about teenagers growing up in contemporary, urban India instead of men and women twice or thrice my age, living and dying a few generations ago.

Conversely, I hugged my English classes to my chest. English was funny, as in Roald Dahl’s short story “The Umbrella Man,” about a young girl, her hypocritical mom, and the strange man they encountered on a rainy day. English was scary, as in the excerpt from Juliane Koepcke’s memoir When I Fell from the Sky, about the eleven days she spent in the Peruvian rainforest after surviving a plane crash that killed everyone on board, including her mother. English was mischievous yet wise, as in Vikram Seth’s poem “The Frog and the Nightingale,” ostensibly about two singers in a bog but really about ambition and envy.

Recently, on social media, I asked my school friends for their memories of our Hindi classes. Did they remember what I remembered? A few did. One did not. She wrote, “I enjoyed our Hindi literature classes because the background of the stories was always relatable to me. I struggled with some of the English books because I couldn’t visualize the countryside and had no idea what the trees looked like.”

*

My husband tells me, “You are a nicer person in Hindi than you are in English.”

I believe him. For everything that English has granted me, it has also been the language of competition and of getting ahead in life. It’s the language in which I was reprimanded at school, especially if my friends and I were caught speaking to each other in Hindi. “This is an English-medium school,” our teachers would say. “Speak in English here.” It’s the language I used in college, at my universities, and during job interviews. Now in writing books, and teaching creative writing, English is also the source of my daily bread and butter, and of my relationships with Americans. It’s the language through which I establish my authority in a classroom, order a cup of coffee, check out books in the library.

Hindi, on the other hand, is the language of my neighborhood crushes. It’s what I use to talk to my best friends from childhood. It’s the first tool I picked up when I stepped out of my parents’ orbit and started school. In fifth grade, when I beat everyone else in my class and got the highest score in Hindi, Baba couldn’t stop telling our friends and family about it.

I don’t think I quite understood his sentiment then. But I get it now. Baba’s pride was related to his relief. Four years ago, it was because of him and his new job that we had been plucked out of Kolkata and I had had to learn this complex new language. And now, here I was, proving that we as a family were okay. That I was okay.

Hindi is also the language of TV shows and films I watched on the first television my parents ever owned. My dad built it from scratch—as a hobby—and named it after my mother. At home, though, Baba insisted we speak only in Bengali. After all, who were we as people if we allowed ourselves to forget our mother tongue?

Halfway across the world from New Delhi, in Los Angeles, my mother-in-law followed the same principle, though maybe she didn’t put it in exactly those words. She spoke Punjabi at home, but her sons—my husband is her eldest—succeeded in sneaking in English. She stayed on top of her second language, Hindi, through movies the family rented from local Indian grocery stores. She couldn’t have known then that two decades in the future, knowing Hindi was going to come in handy when speaking to me, her daughter-in-law.

*

Shortly after my first three months in the US, I realized that watching every Hindi song and movie and ad was not a sustainable practice. Plus, as Ma said, “You are there now. You must immerse yourself in that life. If you keep looking toward here, you will miss out. And that won’t be fair to you or to either of the two places.”

Here, instead, are sustainable habits I have devised over time:

1. Every Sunday, when I meal-prep, Hindi films play in the background. Sometimes, even an hour into the film, I would have not looked at the screen or registered the actors or plot. When my husband walks into the kitchen, he might comment along the lines of, “Your back is turned against the TV. How are you watching anything?” I never have a good answer except, “It doesn’t matter whether I see them or not. It’s my ears that need it.”

2. My spice jars are labeled in Bengali or Hindi.

3. If I have had an especially busy week and all my energy has gone into conversing, writing, teaching, and thinking in English, I will spend most of the weekend binge-watching Hindi movies. A cleanse and a reset.

4. I routinely search YouTube for new and old recordings of Hindi poems. When a poem moves me, whether on account of its words or the deft delivery of the reciter, I jot it down, word for word, in a journal I have dedicated to this purpose.

Does the acquisition of language stall at the point of immigration? Perhaps. I know I have not gone further in my study of either Bengali and Hindi, and my fluency has suffered and taken a back seat. In her essay “Mother Tongue,” Yoojin Grace Wuertz writes, “I imagine that behind every bilingual person there is a story of separation. Of homes left behind, families divided, identities remade over and over again. A history of loss in addition to the mixed gains of the American Dream.”

The switch is not just between words, syntax, and grammar. It’s of something fundamental and rooted in my core.

Cheekily, I want to ask, “What then if you are trilingual?”

*

It’s the winter of 2017, and I am back at my parents’ home in New Delhi. I show up at the dining table and food appears magically. My mother’s perfectly blended black tea, a mix of Assamese and Darjeeling leaves, alights in beautiful cups at regular hours of the day. I write every morning, and in the afternoons, I reread books that were childhood favorites. Most evenings, on his way back home from work, my brother surprises me with beloved snacks we used to enjoy as kids. It’s a charmed life and I have no complaints.

A month later, my husband joins me. This is his first time visiting my family, and I am confident everyone will get along well with everyone. They all get along with me. Why won’t they with each other? Naively, I haven’t considered the language barrier even once.

My mother reads and understands English well but sometimes feels hesitant speaking it. My husband’s English comes with an American accent. My father switches between English and Bengali, as do I and my brother, to make my husband feel included.

It doesn’t work.

Put a roomful of Bengalis or any other linguistic group together and they will switch to their own language despite knowing better and wanting to make the outsider feel included.

Whereas just a few days ago, I had looked forward to my husband’s arrival, I now grow resentful. It’s because of him I am “forced” to speak in English. He is the reason I must translate continuously. In a matter of days we will return to the US, where once again I will be required to speak English 24/7. Why won’t he give me this respite?

More than anything else, I am exhausted from having to constantly translate between two languages. The switch is not just between words, syntax, and grammar. It’s of something fundamental and rooted in my core. It’s as if I inhabit a different mind and body when I speak Bengali or Hindi than when I speak English. Who is the real me, then? What is her preferred language?

*

On a warm afternoon in July 2018, my husband and I entered a tattoo parlor in downtown Moscow, Idaho. I had made the appointment a week earlier, although I had been considering and rejecting designs for years. I couldn’t decide. Should it be the three eyes of Durga, my favorite Hindu goddess? Or the outline of Nautilus, the submarine from Jules Verne’s Twenty Thousand Leagues under the Sea? Or maybe a tiny map of Delhi?

Finally, once I decided, the tattoo artist—a skinny white guy with tattoos all the way up and down his arms, legs, and neck—placed paper cutouts of my selection at various points of my right arm. Nothing fit, nothing seemed right, until he placed it on my wrist.

“Yes,” I said. I had chosen two words, in their distinct scripts: Golpo and Katha, the Bengali and Hindi words for “story.” When the tattooist finished inking, I felt a sweet, if silly, relief. This, right here, was a little reminder, a nudge, that I was still the person I was meant to be. That I was, and will continue to be, in my husband’s words, “nicer in Hindi.” That no matter how my day went, how much of it I spent speaking English, at night I was still going to dream in Bengali. If ever that changes, I will know that the ninety-eight letters I had once learned to read and write have fallen out of the jigsaw board of my mind and rearranged themselves. I don’t know what I will say to myself then or in what language.

__________________________________

From Brown Women Have Everything: Essays on (Dis)comfort and Delight by Sayantani Dasgupta. Copyright © 2024 by Sayantani Dasgupta. Used by permission of the University of North Carolina Press.