When I’m twelve, I have a pet lamb named Wilbur. I feed her powdered milk mixed with water that I funnel into an old beer bottle. She pulls on the rubber nipple, enthralled with me. The green-and-white Labatt 50 label sparkles my palm. The other sheep run from me, but Wilbur thinks I’m her family. She isn’t scared of the dog. Sometimes I let her come inside the house, then pour molasses into the dog food bowl. When I’m an adult and I meet children who are twelve, I often say, Twelve is the best age!

*

My parents taught me to say I’m fine when anyone asked How are you? It doesn’t sound right when I say it, but I don’t know what else to say. I don’t want to bother anyone with my real feelings. My family listens to public radio, plays comedy records, sings folk songs while doing the morning and nightly chores. When I meet people who express sorrow or anger, and explain what they need but don’t get—these are people I want to be around, as though I can wordlessly learn to feel and express feelings by being around their leaking faces, their longing. When adults ask me what I want to be when I grow up, I say an actor. Imagine spending your life pretending to feel everything so deeply. I rent Fame so many times from the rack of VHS tapes at the corner store that Mrs. Johnston tells me to keep it.

*

As a child I spend a lot of afternoons lying on the forest floor, a bed of wet cedar, an audience of softwood branches.

Wilbur is the only one who isn’t afraid of the coyote. I grow up to make films.

*

Going on tour to promote an independent film sounds glamorous, but when you’re thirty-eight and rethinking all your life choices, it just means you’re taking panicked naps in dozens of near-identical hotel rooms. On the last night of touring, I think I see Simon sit down in the front row. I’m not sure it’s him. The lights are too bright. I’m standing onstage wearing the same pale blue dress with the vine-leaf print at the hem that I’d worn for twelve other events. I’m introducing the film, saying the same few sentences I always say, and then I walk up the aisle to pace in the lobby until it’s time to come back again for a Q&A. I’m proud of this film, but I am tired of it. When I watch it, I can only see how it might have been improved. I want to start something new, but I spend most of my time thinking about me and Jamie. How our relationship could last. I have artistic pursuits, but ever since I met Jamie, my one quasi-intellectual pursuit is how one sustains a turbulent love. I turn to poetry. I watch a lot of porn.

Jamie is usually with me at events, but tonight they stayed back at the hotel, working on a deadline. Jamie is a journalist. We spend a lot of time looking up at each other from the glowing lip of our laptops. Right before the screening, I’m trying to get dressed, and they want me again. I just need them to do up my dress. They try to take it off instead. It rips a little. Sorry, they whisper. When I say a firm no, not a playful no that would lead to some kind of fantasy sequence, they flop back on the bed and pop their hand in their pants. A sulking face. I grab my purse and leave, doing my dress up in the elevator.

I’ve been queer for twenty years. It took me a long time to figure out my weakness is for hard-won masculinity. Especially any kind that has an edge of softness. Jamie looks like they’d fight a bear for me. They often want me, in a physical way, but I want them in an emotional way that is unyielding. Sometimes when they’re fucking me, I think that I could probably be anyone and in that moment they wouldn’t care. They’ll always be the one who is more beloved. I know they will one day leave me. I think that keeps me from getting bored. I have only ever loved someone with that kind of intensity once before. And he’s in the front row of the theater, looking twenty years older. Simon.

At the Q&A, I get a lot of questions that the asker thinks are unique but I’ve fielded dozens of times. There’s always one asshole who asks about feminist hysteria. I have quips, snaps, and diversions at the ready. This is the last event. I walk up the waxy wooden stairs and the moderator hands me the microphone. And that’s when I see Simon for real, with the house lights up. He’s bald now. I can’t feel my feet.

*

In 1988, Simon is singing “Jesus Is the Rock” when he grabs my hand. Our pew is crowded with youth group kids, so the sides of our legs are touching all the way down. There is so much happening in my body that being still is impossible. I am almost thirteen. Simon is seventeen. When he leans down to say, Peace be with you, as the minister instructs us to do, I feel his stubble across my cheek. I have never felt more holy.

*

“He’s had a rough life,” my mother tells me in the car on the way to the grocery store. I sit in the backseat with a sheaf of paper in my lap, writing to Simon. My stationery has peaches and butterflies along the border. When you press your nose against the matching envelopes, you can smell pie. I see Simon every few months at the county youth group gatherings. He lives an hour away. That my mom thinks she can tell me anything I don’t already know about Simon is crazy. Of course he’s had a hard life. A hard life is an interesting life. Unlike mine.

I pretend to be tough in my letters to Simon. I write very basic things about being twelve and three-quarters and living on a farm. I write in green cursive. I don’t tell him how much I like to read, or how much I appreciate the town librarian. Our library is in the basement of a church, and there is a corner of it reserved for English books. I’ve read almost all of them. This week, the only book left is a biography of Elvis.

When the new Scholastic Book Club flyer comes out, it’s the best day of the season. I don’t write to Simon about that either.

*

Simon’s letters to me are scrawled in barely decipherable masculine lettering, my name and address on plain white envelopes. They hold so many feelings—about his parents, about the factory where he’s started to work after quitting school, about his friend who had dropped acid and then killed himself. I read them so much they are memorized by the time a new one arrives. I love how he ends the letters. He tells me how much he loves me, how special I am, how beautiful. Beautiful? I’m still growing out a bowl cut, little straggles of dirty-blond hair. My most prized possession is a white lace trainer bra from the Sears catalog. I even wear it to bed, hoping it will help spur growth.

*

Even though I know what it feels like to grip bailer twine inside my fists, I know my hands are going to be soft throughout my life. I’m going to be among books. I’ll go to university and I’ll have options. Kids around here have no options, I hear adults say around the snack table after Sunday school. My brother is starting grade eight. The neighbor comes over to fix the tractor. He looks at my brother and says, “Eighth grade, just about quittin’ time, eh?” My brother wears thick glasses. His favorite hobby is math.

*

When I’m a kid, I think we are poor because there is a hole under the gas pedal of the van we use to haul the sheep, and tufts of pink insulation peeking out from my bedroom wall. I fall asleep to the soft scratching of the mice who live under my bed. But there is something different about us. My mom says “We can’t afford that” about twenty times a day, and the girls at school make fun of my clothes, often my brother’s hand-me-downs. But there is a difference between me and most of the kids I know. It’s something to do with the way my friends grimace when my mom makes carob brownies. I practice dancing like the girls in the Whitesnake videos, but it does not come naturally. My best friend’s parents are in their thirties but don’t have their own teeth. Her mom is one of fourteen children, her grandmother got married at thirteen. My mom says it’s because the Catholic Church hates women.

*

I overhear my best friend’s mom calling my mom uppity. They say “She’s been to college” like it’s an insult.

My mom says, “We’re broke, but we’re not poor.”

*

Sometimes, when Simon is upset about a girl, he calls me. I curl the phone cord around my wrist, pulling it as far away from the base in the living room as I can, and lean against the near-closed bathroom door. He often cries. I say, “Simon, I love you.” There is usually a long pause, and then he says, “You’re the only one who really does.”

*

“You know Simon is a man,” my mother says. “He dates women his own age.” We are driving through the flattened hay of a makeshift parking lot at the county fair.

“His girlfriend’s name is Tammy,” I say, proving to her that I know some things too.

*

A few months later, his letters stop coming.

“I hear Simon went off to the army,” my mom says at dinner. “I saw his mom at the mall. He’s going to Kosovo soon.”

*

When I am sixteen, Simon visits me on the farm. He has been overseas for several years. Now that I’m older, he could have expectations. It settles in my chest like a mildly pleasant pressure. Years later I will understand that Simon’s appeal was largely his unavailability. There was no possibility of queerness, so I settled for distance and fantasy and never having to deal with a real boy. Real boys, in my class, were mostly unappealing. Unless one had a crush on me, which gave me something to talk to other girls about.

*

At the time of Simon’s visit, I have a boyfriend I feel ambivalent about. I haven’t felt a real attraction to anyone since Simon, mostly because I don’t yet understand that the operatic feelings of loyalty I have toward my best friend mean something. I’m hungover because in order to have sex with my boyfriend I have to drink an entire bottle of wine. When Simon tells me on the phone that he got married, I feel a strange mix of jealousy and relief.

*

He shows up on a Saturday afternoon. When we hug, it feels as if I am made of carbonation. There is something between us, and that something makes it very clear that there is nothing between my boyfriend and me.

I show Simon my tattoo of a peace symbol. I tell him about how I don’t think we should kill people in the Middle East for oil and corporate interests. The Gulf War is raging. He says, “I figured you and I might disagree about that. It’s hard being over there. I saw a lot of things I can’t unsee.”

*

As he drives down the two-lane highway that leads to town, I can tell that Simon is sad in a way I’ve never seen anyone sad before. He drives too fast. I don’t know what to say as he swerves across the white highway line and back to our side. He doesn’t apologize. He doesn’t seem to notice. I grip my seatbelt.

“I missed you,” I say, and when I say it, I realize I’m testing him. He smiles, but lays heavy on the gas.

“I missed you too, kid. Thinking about you has gotten me through a lot of hard times.”

I am pleased to hear this. I have made an impression; someone thinks of me when I am not there. Simon guns it again. A semitruck is approaching us, we are too close to the middle line. The truck blares its horn, and Simon moves at the last moment.

My voice is higher than I want it to be when I ask, “Are you okay?”

“Don’t worry, baby, don’t worry,” he says to the windshield. “I only go as fast as makes sense.”

We fly by the trailer where Cathy lives. Her mom is in the yard hanging flowered bedsheets, and normally I’d wave to her, but we’re going so fast she’s a blur. I think about how many miles we are from town, from having to stop at a light. The town has only two lights. I wonder if I should jump out at one.

*

Simon is worried his marriage is ending. He’s fucked up now. I want out of the truck. But I keep smiling, flirting, even though he is scaring me. I stick my chest out, I curl one string of hair around my finger.

“Why don’t we stop the truck?” I ask. He doesn’t answer.

“I’m going to throw up.”

He finally hears me and pulls the truck up to a lookout area. We stop so fast my seatbelt feels like a knife. No one ever uses this place except teenagers at night. Simon takes a deep breath. His hands are still gripping the wheel. I go to open the door, but it’s auto-locked.

“Let’s get out?” I say in a sunny way, as if the drive has been completely normal.

“Sorry,” he whispers.

But he doesn’t open the door. Instead, he turns on the radio. It’s a heavy metal ballad from about five years ago. We danced to it at a youth group party.

“I like this one. It reminds me of you.”

“Me too,” I say, hiding one hand behind me, pulling on the door handle so hard I fear I might break it off.

“Your boyfriend, he treats you well? I hope your boyfriend treats you well. You deserve the best.”

I don’t know what to say to that. I don’t treat my boyfriend well. I find him boring, but I can’t do anything about it. There are only six boys in my grade ten class and I’m related to three of them. I had to date someone, so I chose a classmate’s older brother. Simon is only a year older than my boyfriend. When I look at Simon, I feel older than him, though he is now married, and he has, presumably, killed people.

“I need to go outside,” I say. “I’m going to be sick.”

“Oh,” he says, as though just waking up. He clicks the lock and I stumble out. I run toward a bush and hide behind it. Once I’m there, I don’t need to throw up anymore. But I lean over as if I do.

*

It’s too cold to walk anywhere from here. I could follow the riverbank into town, but it gets rocky. And it would be melodramatic. I look back. He is leaning against the front of the truck and has lit a cigarette. He looks normal again. I remember reading vespers together at night at youth camp. He opens a pack of Export A’s and offers me one as I approach the truck. I make a show of wiping my mouth as though I’d just thrown up.

I shake my head.

“You must really be hungover,” he says.

I want to say, I’m carsick from you driving like a maniac, but I don’t. I need to keep everything calm. I lean against the front of the truck too. The song is ending inside.

“You’re so lucky to be young. You haven’t made mistakes yet.”

He puts his hands on my hips, a thumb through a belt loop of my burgundy corduroys. I lean my face against his chest, the way I used to. Even though I’d just contemplated hypothermia to get away from him, my body responds the way it always has. He holds me closer, our bodies pushed together completely. When I stand this way with my boyfriend, he gets hard right away, but I don’t feel that from Simon.

I’ve learned to pause in moments of extreme feeling to see if it’s a real feeling. It usually isn’t. But this is.

*

On the way home, he drives slower. He puts one hand on my leg as he drives, lightly moving a few fingers up and down just above my knee. I want to ask, Are we soulmates? I have flashes of the night before, in my friend’s basement, my boyfriend taking me from behind up against a chest freezer. Even after the wine, it was awkward from start to finish. What Simon is doing, just touching my leg, makes me want to take my clothes off. I look out the passenger seat window, at the trees flickering like an old film reel. I catch glimpses of a deer, a rusted-out car, a coyote.

I want him to move his hand up farther, but he doesn’t. I start to feel as though I have never wanted anything more. I pretend to adjust in my seat, so his hand ends up a little higher on my thigh. I press my lips against my fist. I can’t control the way I’m breathing or understand if it’s loud enough for him to hear above the roar of his pickup truck on the gravel. He taps his fingers to the music, moving higher up. We hit a bump and his hand moves up by accident, knuckles me soft in a place, but it’s only there for maybe two seconds before he puts both hands back on the wheel to turn into our driveway. In that second, I am coming in waves, squeezing my legs together, completely undone. I have never had an orgasm before.

*

We both look ahead for the last few hundred yards up to the house. I don’t know if he knows. I am stunned, running my shaking hands through my hair. When he stops the truck, we see my mother raking up leaves in the front yard. The neighbor has dropped off their four-year-old, who I look after every Saturday night. He is jumping in the leaves. I want to kiss Simon, but we hug instead. He looks almost impatient for me to get out of the truck, so I do.

*

I feel a tenderness for my mother that I don’t express as we both watch Simon drive away.

“How was the visit?” “Fine.”

*

Two years later, I will come out at college because a girl with a buzz cut will kiss me at a ladies’ night, mouths sticky with kamikaze shooters. I’ll remember that feeling from the pickup truck and all the pieces will fit together. When she breaks up with me, I will be so distraught that I’ll drink nearly a whole bottle of tequila and kneel down in the middle of a busy street while it pours rain, daring cars to hit me.

*

Instead of walking down the stage steps the way I usually do, I exit through the side door, into the green room with its room-temperature bottles of water and abandoned Styrofoam cups. Later my publicist hands me a note from Simon. Congratulations! You’ve come so far! His phone number. That same masculine scrawl. I slip it into my wallet. I don’t call.

*

When I get back to the hotel, Jamie has not written one word in my absence. I don’t tell them about Simon. They are curled over a “Stepbrother Wakes Me Up!” video. We act it out for hours. At some point they say, “I think we should get married.” I can’t tell if they are using their fantasy story voice or their real voice.

*

As dawn flickers through the hotel window that will never open, Jamie tells me a story about hitchhiking on boats when they were young. When I talk to them, I have no choice but to use my real voice. I give them all of me, every vulnerable, shaky word. When Jamie talks, it’s as though I’ve never listened closely to anyone else before. Everything they say is gold. Have you ever been talking to someone and thought, Oh, this is my real voice! These are my true thoughts! It’s rare for me to feel that way. But when I do, it endears me to whomever I’m speaking with. I want to ask Jamie: Do you also feel unguarded and absolutely yourself right now? In the majority of my conversations I am bending around. I speak the way they speak. I change my words. I change my tone, trying to be understood, avoid conflict, and make them like me.

Jamie pauses the story. They look as though they might fall asleep. And then they say, “I think I need to be alone. I love you, but not in the right way.” They put their head between my legs and ask if they can sleep there. “I adore you, I adore you,” they say as they fall asleep.

*

We go to a dear friend’s wedding, and I cry through the ceremony. When we get in the car, Jamie says it’s definitely over. They’re looking at me the way someone looks after they come and sex becomes indecipherable. I’m the movie that keeps playing and as you fall asleep, you notice the porn actors look tired or restless, when minutes earlier they were everything you ever wanted to look at. All that fake, holy screaming.

*

No adult can abandon another adult, says the codependent reader in the bookstore where I walk the next day. I take a photo of the page because I am struck by this sentence. I feel abandoned by Jamie, but maybe it is not possible. You’re allowed to change your mind about anyone. There are so few people I get attached to that, when I do, it feels like they’re murdering me if they leave.

__________________________________

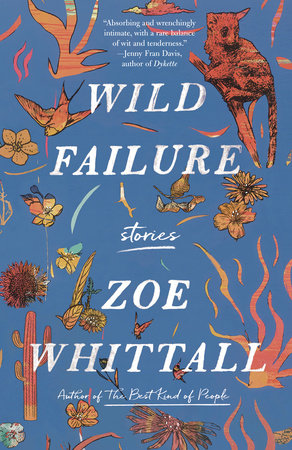

From Wild Failure: Stories by Zoe Whittall. Used with permission of the publisher, Ballantine Books. Copyright © 2024 by Zoe Whittall.