When the Bob Dylan early-years biopic A Complete Unknown arrives in December, with Timothée Chalamet in the title role, Greenwich Village’s role as an incubator for music, poetry, and politics in the Sixties will again be cemented. As it should be: In basements or coffeehouses that barely held fifty people, that era was a veritable hot house of musicians who invented the super-personal singer-songwriter mode, pushed jazz to previously unimagined limits, and injected topical songs into the mainstream.

Article continues after advertisement

But as I was reminded repeatedly during the four years I spent researching and writing Talkin’ Greenwich Village: The Heady Rise and Slow Fall of America’s Bohemian Music Capital, the Village music scene hardly started then; in fact, it went back even further than the stories I’d heard of Billie Holiday singing “Strange Fruit” at the long-gone Sheridan Square club Café Society in the Thirties. Classical music concerts were held in Washington Square Park in the nineteenth century, for instance.

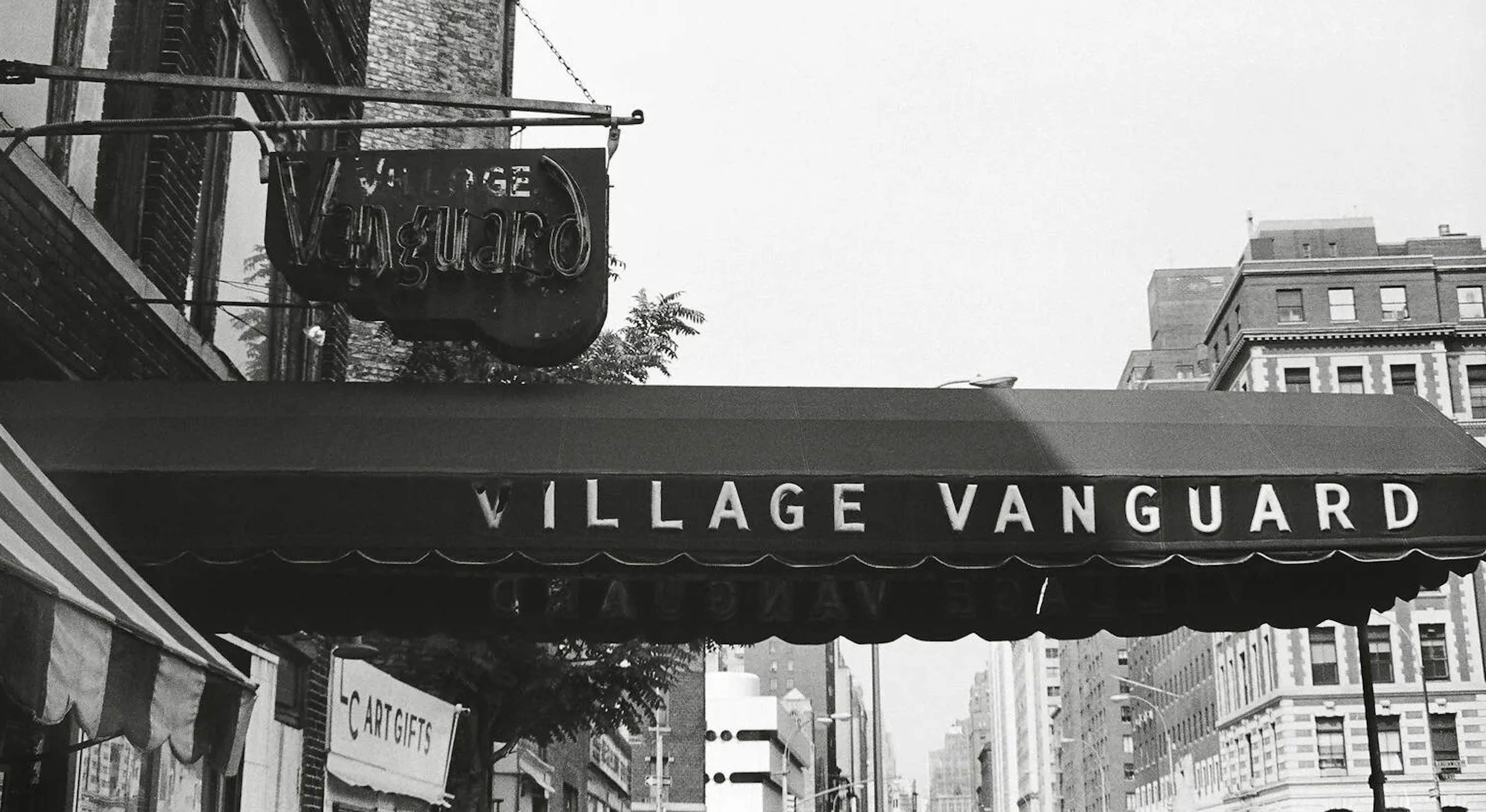

And just under a hundred years ago, the Village’s reputation for attracting iconoclastic, subversive and leftist writers began extending to its music scene. Venues such as Café Society and the Village Vanguard attracted multi-racial crowds who reveled in satirical songs, earthy folk and blues, and pre- and post-World War II jazz.

As I dug into city records and personal archives, it also became apparent that the issues that would plague that world—draconian cabaret laws and the way the city, police and the Mob imposed themselves on the scene—were also in place back then, sowing the seeds for the Village music community’s emergence and decline.

*

True to its neighborhood and its reputation for attracting political and cultural iconoclasts, the space had its own idiosyncratic origin story. To serve the city’s west side, a new subway line had been constructed in the 1920s.

Just under a hundred years ago, the Village’s reputation for attracting iconoclastic, subversive and leftist writers began extending to its music scene.

Because it would snake through the Village, a slew of buildings were torn down or sliced in half to make room for tunnels and stations. As a result, one of those structures, at 178 Seventh Avenue South, now resembled a pie cutter; [Max] Gordon soon learned why its previous incarnation—a speakeasy, the name for burrowed-away joints and spaces illegally selling alcohol—had been called the Golden Triangle.

Retaining the Village Vanguard name, he rented the space—with a cash infusion from someone he later called a “shylock who liked the idea of a club because he thought he could pick up women there”— and moved whatever was inside the first space to the new one. As he was preparing for its grand opening on February 22, 1935, a cop walked in, saw that Gordon was using beer cases for seats, and asked, ominously, if he was selling alcohol, which required a liquor license.

“Let me sell the beer,” Gordon replied. “Then I’ll have the money to pay for a license.” He was off the hook, at least for a while.

Since its inception, Greenwich Village had functioned as both sanctuary and battleground. Galleries, small presses, and enough writers with enough works to line the shelves of a small library were drawn to its narrow, crooked, often con-fusing streets and ambience.

At various points, Mark Twain, Edgar Allan Poe, Edith Wharton, O. Henry, and Henry James had called the Village their home; Herman Melville worked at the US Customs Office there. Willa Cather, Eugene O’Neill, Theodore Dreiser, and Stephen Crane all bunked at one time or another at the so-called House of Genius on Washington Square South.

Even the geography of the area played into that image: as historian and onetime Village Voice editor-in-chief Ross Wetzsteon would later write, the sheer bewildering layout of the Village—especially the new grid laid out in 1811 that overlapped with the meandering streets of the Village—had “metaphoric resonance as well: rejecting orderliness, refusing conformity, repelling the grid.”

The ethnic groups and factions that came in and out of the area had periods of cooperation and intermingling. They could also clash, as when the Lenape indigenous people who had called it home eventually battled with Dutch settlers in the middle of the seventeenth century. In time, the Village’s developing music community would prove to be equally turbulent, if not as violent.

Although it would be difficult to determine the first or earliest venues in Greenwich Village, music clubs began appearing in the early twentieth century. In 1919, weeks after the U.S. Senate overrode President Woodrow Wilson’s veto of the Volstead Act, which prohibited the sale of alcohol, police raided the Greenwich Village Inn, a speakeasy on Sheridan Square.

The spot was managed by Bernard “Barney” Gallant, a restaurateur and member of the New York Liberal Club, a prominent debate and discussion group. Gallant became a local hero when six staff members at the inn were arrested for selling hard liquor to undercover police; to spare his staff, Gallant himself spent several weeks in the Tombs, the city’s notorious jail.

That notoriety extended to the Greenwich Village Inn Orchestra, such a sensation that an uptown radio station ran wires down to the club to broad-cast its melodies on the air. Thomas Edison’s phonograph company soon issued Greenwich Village Inn Orchestra recordings, such as the peppy foxtrots “Somebody’s Crazy About You” and “Keep on Dancing.”

Meanwhile, customers at nearby bistros might have heard the district satirized in song by Bobby (or Robert) Edwards, the so-called “Bard of Bohemia” who’d graduated from Harvard and moved to the Village in 1904. In his lengthy ballad “The Green-wich Village Epic,” he eagerly skewered the area as “the field for culture’s till-age / There they have artistic ravings / Tea and other awful cravings.”

In the middle of Prohibition, the cocktail of the Jazz Age, speakeasies, illegal alcohol, public dancing, and white and Black crowds commingled in bars and clubs was too much for the wealthier and more politically connected part of New York eager to control that type of conduct.

When it was first put into effect on January 1, 1927, Local Law 12, otherwise known as the “Cabaret Law,” was a reaction to illegal bars and sought to put constraints on what it called a “public dance hall” or a “cabaret.” The latter was defined as “any room, place, or space within the city where any musical entertainment, singing, dancing, etc., is permitted as part of the restaurant business or the business of selling food or drink.”

To obtain a cabaret license, which cost $50 a year, owners had to pass through a gauntlet of inspections from the build-ing, licensing, and health departments, and businesses would have to close between 3 a.m. and 8 a.m. (Decades later, it would be alleged that the inter-racial dancing in clubs, especially in Harlem, may have also given rise to the law.) When the law was amended in 1931, another layer of bureaucracy was included: the issuing of licenses was transferred to the police commissioner, who was also tasked with inspecting each venue.

Even before he allowed his first customers into the Village Vanguard, Gordon learned how the new law worked. After he’d graduated from Portland’s Reed College in 1924, Gordon moved to New York to attend Columbia Law School but was stranded in the city without a job after he decided not to pursue a law career.

Encouraged by a friend, he borrowed some money and opened a coffeehouse, the Village Fair, on Sullivan Street, in 1932. There he hosted poets and writers and learned firsthand about the tricky and sticky relation-ship between the neighborhood and the police, even during the waning days of Prohibition.

Since clubs weren’t allowed to sell booze, Gordon, as he later wrote, would always see “a guy in a doorway hanging outside Village joints” who could supply a bottle of some libation, which could then be taken inside. Gordon ended up under arrest after an undercover cop convinced a waitress to buy some alcohol, then bring his bottle of booze to him while he was inside the Village Fair. The charges against Gordon were eventually dismissed, but it was too late to salvage his business.

As a columnist of the time put it, Gordon’s new Village Vanguard on Seventh Avenue South lay “at the foot of a gloomy flight of stairs,” but the murk lifted once customers looked around. Its light- blue walls were festooned with murals depicting horses playing a piano and women floating through space, and the entertainment Gordon served up was equally lively.

Reflecting the Village’s nonconformist inclinations, the Vanguard also became headquarters for some of the city’s most insubordinate art.

Early on, poets, including Harry Kemp and Maxwell Bodenheim, dominated the lineups. By 1937, Walter Winchell, the syndicated columnist, snarkily commented that Saturday nights at the Vanguard were filled with “‘bohemians’ from Brooklyn and the Bronx squinting through the soupy smoke.”

Reflecting the Village’s nonconformist inclinations, the Vanguard also became headquarters for some of the city’s most insubordinate art. At the end of the thirties, the Revuers, a comedy posse that included Judy Holliday and Adolph Green, began working up satirical songs and skits. As with its parody of the upscale Cue magazine and its listings, the sketches often took aim at the uptown crowd.

Also at the Vanguard, a group that called itself the Calypso Singers mocked Wendell Willkie, the presidential candidate who’d switched from the Democratic Party to the Republican (he paid “an income tax that’s not too alarming,” they sang). Meanwhile, their version of “Netty Netty,” a naughty slice of calypso meets swing, included bedroom-frolic lyrics that, Winchell wrote, “will make you blush.”

___________________________________

Excerpted from Talkin’ Greenwich Village: The Heady Rise and Slow Fall of America’s Bohemian Music Capital ©2024 David Browne and reprinted by permission from Grand Central Publishing/ Hachette Books /Hachette Book Group.