On a muggy August day, as people traverse the Brooklyn Bridge, families congregate for ice cream in a former twentieth-century fireboat house, and tourists line up outside Grimaldi’s Pizzeria where Front Street meets Old Fulton Street. All the while, the cacophony of modern traffic from the Brooklyn and Manhattan Bridges and the much-unloved BQE (the Brooklyn-Queens Expressway, to the uninitiated) pierces their senses. This is Brooklyn—“Like No Other Place in the World!” The convergence of these people, places, and sounds obscures that here is where the heart of the Village of Brooklyn once stood, home to a “casual collection [of residents] from all quarters” who mostly lived around the Fulton Ferry landing.

Article continues after advertisement

The Village of Brooklyn

Brooklyn was settled along the path leading from Marechkawieck that became known as the road from the ferry in what is today’s Brooklyn Heights. In 1704, under an act passed by the General Assembly of the Colony of New York that required the creation, regulation, and maintenance of new highways, the road would become the town’s main street and be renamed Fulton Street. In the late eighteenth century, one traveler observed that the town of Brooklyn had about one hundred one-story dwellings.

Almost all of the village’s activity, its structures, and its residents were centered around the northwestern end of town, near the ferry landing where, by 1814, Robert Fulton’s steam ferry revolutionized travel across the East River by significantly reducing travel time between Brooklyn and Manhattan. Most of Brooklyn’s dwellings were frame, or made of wood, though some wealthier residents constructed their businesses and homes using more expensive brick or stone. The “unusually healthy” air was otherwise accompanied by the unpaved walkways that frequently became muddy after it rained. Over the next three decades, the one-square-mile village transformed from farmland to an emerging urban development based on land speculation.

In spite of virulent racism, this diverse community of early Brooklynites lived in close quarters and inhabited the same streets and public spaces.

The village contained ropewalks, taverns, stores, one-story homes, and unpaved streets (with the exception of Fulton, which was paved in 1822). Whereas in 1800, some foodstuffs, for example, corn (maize), might have still been grown in Brooklyn’s fertile soil, by 1822, villagers’ diets were not necessarily tied to the local land or weather (though corn long continued in other parts of Kings County, such as New Utrecht, that remained largely agricultural throughout the nineteenth century). Instead, Brooklynites had access to a variety of foodstuffs even in the absence of a singular public market like the thriving Fulton Street Market across the river in the City of New York.

The village was home to six butcher stalls (three on Main, three on Brooklyn’s Fulton Street) and a fish stall on Fulton near Front, and vegetables and poultry could be found at a number of grocers dotted throughout. One such grocer, G. C. Langdon, who had moved from Manhattan to Brooklyn, sold hams, smoked beef, “Indian currie and other seasonings,” white Havana, East India, and brown sugars, Holland gin, teas, and “superior Spanish segars” at his store on Fulton Street next to the Steam Boat Hotel. Myriad regulations governed the behavior of the residents of the small village, from the quiet observance of Sundays to the roaming and use of sheep, bulls, hogs, horses, or carriages to the use of guns, pistols, crackers and fireworks, and firing at marks or targets with ball or shot to businesses of inn holders and cartmen to fires and nuisances, bathing, dirt, and the cleaning of streets (in the absence of central sanitation services, each resident was responsible for their own gutters and the public street in front of their homes).

The English painter Francis Guy arrived in Brooklyn in 1817, just one year after the village was incorporated into the former colonial town of the same name. Brooklyn could not have been more different from Manhattan at this time. Manhattan, or the City of New York, had long established its social and economic status in the United States and in the Atlantic world. In Tontine Coffee House (1797), Francis Guy had depicted Manhattan as a modern industrial space (it had already achieved city status, whereas it would take Brooklyn another three-plus decades to do the same).

Urbanized and developed, the busy commercial waterfront in the distance makes clear the business of the buildings at the painting’s right along Wall Street and the workers at its center. To the left, the grand brick Tontine Coffee House is a gathering place for merchants, brokers, and businessmen whose affairs were intimately tied to the sale of slave commodities such as sugar, rum, and cotton. Manhattan’s skyline, already standing so much higher than Brooklyn’s, exemplified North American capitalism. When Brooklyn eventually received its city charter in 1834, the mechanics of its own urban operations remained entirely distinct from its East River neighbor, as did its sounds, sights, and smells.

In 1820, Francis Guy captured the village in the dead of winter from his studio on Front Street, in a painting titled Winter Scene in Brooklyn. Francis’s gray winter sky wraps around the busy village of uneven, diagonal streets lined with frame dwellings—homes, stables, and businesses belonging to its residents, who themselves represented a diverse cross-section of class, gender, and race. These residents included Irish immigrants, transplants from New England, descendants of mostly English colonizers, and to a lesser extent the original Dutch (who lived in larger numbers further out in Kings County), free people of African descent, and in smaller numbers enslaved people of African descent too. By 1820, almost all of the Indigenous Lenni Lenape were either murdered or displaced. In spite of virulent racism, this diverse community of early Brooklynites lived in close quarters and inhabited the same streets and public spaces. They resided in neighborhoods that are known today as Downtown Brooklyn, Brooklyn Heights, DUMBO, and Vinegar Hill.

Francis Guy (American, 1760–1820), Winter Scene in Brooklyn, ca. 1819–1820, oil on canvas. (Brooklyn Museum)

Scholars have written extensively about the village residents seen and unseen in Francis Guy’s Winter Scene. The painter identified almost all of the Brooklynites of Dutch and English descent, including Abiel Titus, Mrs. Burnett, Judge Garrison, Jacobs Hicks, and Judge Sands, even as he failed to identify the Black Brooklynites who were also clearly visible. In doing so, Francis makes some Black Brooklynites hypervisible while simultaneously securing their erasure. Henry Stiles, Brooklyn’s self-appointed nineteenth-century historian, later identified Samuel Foster, a chimney sweeper who appears on the painting’s far right, and another Black man, Jeff, who stands between his enslaver Abiel Titus, who is feeding chickens, and Mrs. Burnett, who speaks to Abiel’s son on horseback.

Other Black residents include a man who has fallen on the ice while a dog stares at him and another two engaged in hard, manual labor bent over the logs in the painting’s front left. These residents are not afforded the luxury of standing and chatting with their neighbors as the white Brooklynites in the scene do. This “casual collection from all quarters,” as Timothy Dwight, who had served as Yale’s president from 1795 to 1817, observed, included a thriving free Black community. Its residents included Elenor and Elizabeth Croger and their husbands, brothers Peter and Benjamin Croger, respectively. They lived at a time of both tremendous urban growth for the village and, because of gradual emancipation, formidable challenges too.

The Crogers of the Village of Brooklyn

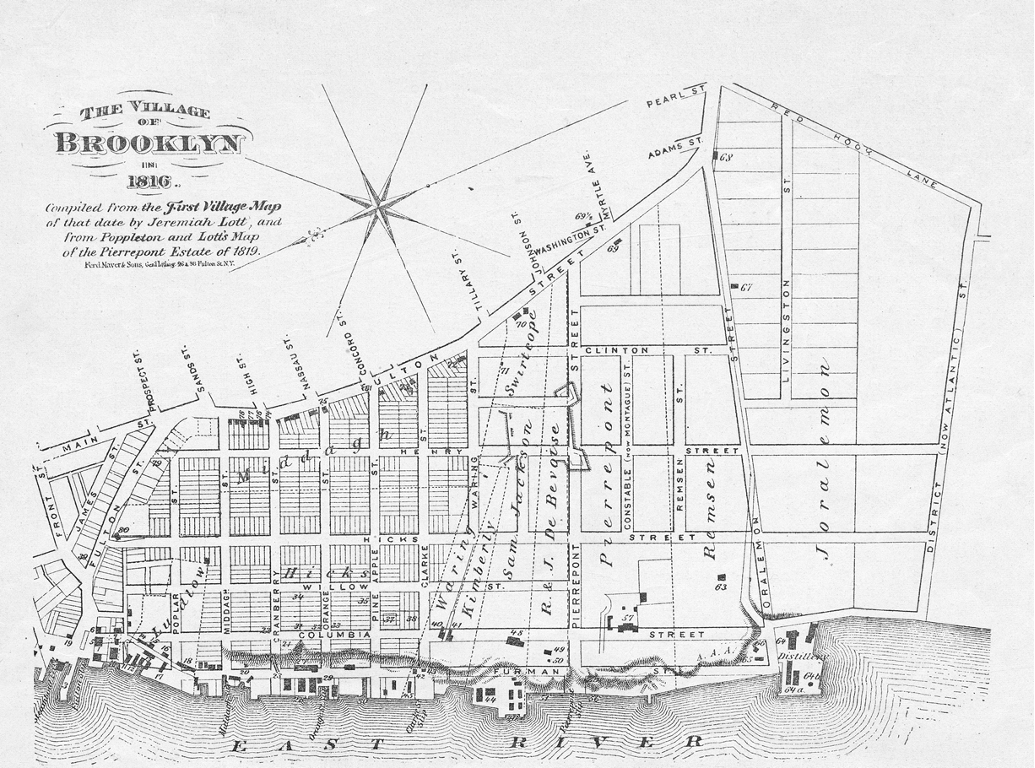

The Village of Brooklyn—the town’s most built-up area—lay at one square mile in 1816 when Jeremiah Lott created his map. It was bound by the “Public Landing south of Pierpont’s Distillery, formerly the property of Philip Livingston, deceased, on the East River; thence running along the public road leading from said Landing, to its intersection with Red-Hook Lane; thence along said Red Hook Lane to where it intersects the Jamaica Turnpike Road; thence a north-east course to the head of the Wallabout Mill-pond; thence through the center of the Mill-pond to the East River; and thence down the East River to the place of the beginning.” Members of its small, but significant, free Black community lived among their white neighbors, in an integrated area bound by Bridge Street, Sands Street, Fulton Street, and the East River, with the largest concentration in a triangle that no longer exists between Old Fulton, Main, and Front Streets. This is where the Croger families lived in the early nineteenth century.

Although brothers Peter and Benjamin Croger were born free in Manhattan, their move to Brooklyn around 1806, together with their partners, Elenor and Elizabeth, respectively, signaled new energies in the town. Fragments of their lives appear in census and probate records, city directories, and newspapers. While these records are the fabric of the historian’s craft, the archives cannot fully convey the immeasurable impact they had on their city, and relying on them alone offers a cautionary tale, as the lives of sisters-in-law Elenor and Elizabeth Croger are almost entirely erased. I seek to honor them in their gifted capacity as “young black women [who were] radical thinkers” and “tirelessly imagined other ways to live and never failed to consider how the world might be otherwise.”

Peter, Elenor, Benjamin, and Elizabeth would shape the political landscape of Brooklyn through their radical activism. Though there are no known written birth records for Elenor or her husband, Peter, or Elizabeth and her husband, Benjamin Croger, we know from the 1850 federal census (with the exception of Peter, who had died two years earlier) that they were born at a revolutionary time in the Atlantic world. Elenor was born in 1783, at the end of the American Revolution. And Elizabeth and Benjamin were both born in 1789, which marked both the beginning of the French Revolution and the publication of Olaudah Equiano’s Interesting Narrative, an autobiography that laid out slavery’s horrors and demanded freedom across the Atlantic world. Although we have no written accounts, we can also assume that Peter, Elenor, Benjamin, and Elizabeth heard tales in their childhoods of Black liberation through news of the Haitian Revolution that began in 1799. In other words, they grew up at a time in post-revolutionary New York in which the ripples of radical freedom were being carried back and forth across the ocean’s currents.

Jeremiah Lott, The Village of Brooklyn in 1816, 1816, map. (B P-1816 (1816–?).Fl, Map Collection, Center for Brooklyn History, Brooklyn Public Library)

Jeremiah Lott, The Village of Brooklyn in 1816, 1816, map. (B P-1816 (1816–?).Fl, Map Collection, Center for Brooklyn History, Brooklyn Public Library)

The first federal census began in 1790, but the Croger households do not appear in the 1800 or 1810 census records. While national events saw the tumultuous passage of the Missouri Compromise in 1820, which admitted Missouri as a slave state, admitted Maine as a free state, and prohibited the expansion of slavery above the 36°30′ latitude line in the remainder of the Louisiana Territory, closer to home, the year also marked the earliest federal census detailing the Croger household. The record is interesting for what it does and does not tell us. We know, for example, that there was a free Black man named Peter Croger living in the village of Brooklyn, aged somewhere between twenty-six and forty-five years old, as per the census columns. There were no children listed in the household, and that remained the case until Peter’s and Elenor’s deaths, according to the couple’s will and probate records.

We also know from the 1820 census that Peter lived with a free Black woman in the same age bracket. Though there is no name listed, it was more than likely his wife, Elenor. However, we do not know Elenor’s maiden name from this census record (later probate records list her as Croger, and no birth or marriage records have been found to date), where Peter and Elenor were born (that would come from later records), or the type of labor the couple engaged in (that appears in other contemporary records). But we do know that the Crogers lived on Pearl Street in 1820, a street that ran from the East River to the long-covered lanes that made up the village’s numerous ropewalks, where baskets and rope were made.

Today, centuries of urban development have erased the street’s original hilly topography, destroyed the bountiful oysters from the nearby East River that lined the village’s streets and gave rise to the street’s name, and truncated the original Pearl Street that connected the village of Brooklyn north and south. But in 1822, the residents of Pearl Street, according to the city directory, included an eclectic mix of slaveholding families, self-appointed village leaders, white female property owners, and free Black Brooklynites. There were no enslaved people resident on the street, according to census records. Black families along Pearl included the Croger family and neighbors Cornelius (89 Pearl), Samuel Anderson (93 Pearl), Henry Brown (91 Pearl), and Titus Roosevelt (85 Pearl). The street was also home to white families such as William Burnett (a fur dresser at the back of 84 Pearl) and Peter Haley (a mason at 65 Pearl). Peter and Elenor lived at 90 Pearl Street, and Benjamin and Elizabeth lived at number 91, though it is difficult to say if the two residences were next door or opposite to each other, as there was no standardized enumeration of houses at this time.

Black Brooklynites embarked on a path of self-determination and created their independent institutions for community building, growth, and celebration.

It is vital to acknowledge a few erasures here. The year 1822 marked the first year that Brooklyn commenced regular publication of its city directories—up until this point, there had been limited sporadic attempts by various village residents. Alden Spooner, a New England transplant, served as the directory’s publisher. His print shop, centrally located at 60 Fulton, published a number of small-run pamphlets and was also home to the Long Island Star (it would become Brooklyn’s oldest and longest-running newspaper), which he had bought in 1811 from fellow local printer Thomas Kirk. Alden also possessed significant power in the village as a publisher and court surrogate and in his leadership positions at central organizations such as the Brooklyn Lyceum and the Brooklyn Gas Light Company.

Alden’s choice, keeping in line with other city directory conventions at this time, to list alphabetically the head of household (usually the male home owner) and no one else meant that we therefore only have a partial glimpse into the complex class, gender, ethnic, and racial composition of Brooklyn at this time. Boarders, renters, villagers with any housing insecurity, and Black women faced complete erasure from this type of historical record. Moreover, it is important to note that all the white men are listed in the city directory along with their line of work (although they are not designated as white, that is assumed by the publisher). Spooner, for example, is listed with his profession alongside his home address and any visible leadership positions he held in the formal running of the village.

Whereas, except for Titus Roosevelt, who is listed in the city directory as a ropemaker—presumably given rope’s centrality to Brooklyn’s early economy—all of the men of color are listed as “black,” and no jobs are printed next to their name. The print strategy in Alden’s directory, then, made the racialization of Black men hypervisible, while making invisible the racialization of white men as the default or norm. It also erased from Brooklyn’s history how Black labor critically supported the village’s economy through everyday low-wage skilled work or its own radical community building.

We know from later census records and advertisements placed in the Long Island Star that Peter and Benjamin worked as whitewashers most of their working lives. Whitewashers were essential laborers in a village like Brooklyn, as they mixed and applied a whitewash compound of slated lime and water to barns, fences, gates, walls, or ceiling, resulting in the upkeep of the village’s dwellings as they exhibited a bright-white paint. But racism restricted Black Brooklynites to a limited labor market, and no doubt Pearl Street’s residents worked low-wage menial jobs that forced them to live on, or below, the poverty line, like so many other Black residents across Brooklyn and New York. From census records, city directory listings, and newspaper advertisements, we know that Black New Yorkers worked as blacksmiths, boot blacks, cartmen, dock workers, general laborers, and whitewashers.

Despite the struggle for a wider variety of jobs that might have showcased their skills and ability to earn higher wages, residents of Brooklyn’s free Black community radically organized their labor to serve in an additional public capacity as grassroots church elders, community leaders, educators, and organizational officers. Black Brooklynites embarked on a path of self-determination and created their independent institutions for community building, growth, and celebration.

In the “Organizations” section of the 1822 city directory, Peter is listed as a preacher of the African Methodist Church and class leader of the African Methodist Church. In some capacity, print culture such as Spooner’s 1822 city directory gave voice to Black Brooklynites’ labor and participation in civic life, even as they were excluded from holding formal leadership positions or positions of formal office as clerks, constables, high commissioners, overseers of the poor, and town officers in the growing village. Self-determined participation in civic life would prove to be critical during gradual emancipation in New York from 1799 to 1827, in which Brooklynites and others witnessed the slow dismantling of slavery in New York, the upholding of slaveholders’ economic interests, and numerous legal measures that were not designed to improve the economic, political, and social needs of people of African descent, both enslaved and free.

__________________________________

Excerpted from Brooklynites: The Remarkable Story of the Free Black Communities That Shaped a Borough by Prithi Kanakamedala. Copyright © 2024. Available from NYU Press.