Originally published in 1999, Broke Heart Blues was my valentine to the intoxicating nostalgia of high school in Williamsville, New York, from which I’d graduated in 1956.

Article continues after advertisement

The novel is told by a chorus of naively besotted voices, each of them focused upon the memory of the most intense, the most wonderful, the most intensely wonderful and terrifying years of their lives as American adolescents in a sequestered affluent community called “Village of Willowsville, New York, population 5,640, eleven miles east of Buffalo”—almost exactly a mythic replica of Williamsville as I remember it; not just the regal-looking redbrick high school but the surrounding suburban community, so unquestioningly a bastion of (white) privilege it seemed to float in a netherworld beyond even complacency.

Here is, I would suppose, an absolutely faithful portrait of upper-middle-class American suburban life in the 1950s: not a cruel satire, or any sort of satire at all, but rather a tenderly observed comedy of manners, a more realistic portrayal of American life of that era than its representation in the much-loved illustrations of Norman Rockwell.

(It should be acknowledged: I did not live in Williamsville but in what was called “the north country”—some miles north of Williamsville in a rural region characterized by much less affluent households and struggling small farms like the one owned by my grandparents, where my parents, my brother, and I lived during the era of Broke Heart Blues in a farming community called Millersport, no more than a crossroads on Transit Road as it crossed the Tonawanda Creek into Niagara County, overall a much less prosperous county than Erie.

In the novel it is negligently mentioned that “hicks” from the north country were bussed to Willowsville High, and so it was, just a few of us living in northern Erie County were brought by school bus to Williamsville, where we were made to feel the distinction, the difference, between the rigors of the north country and the idyll of suburban Willowsville.)

In Broke Heart Blues there is no individual who represents the author, perhaps an oddity in a novel so steeped in nostalgia.

In Broke Heart Blues there is no individual who represents the author, perhaps an oddity in a novel so steeped in nostalgia. If there is an authorial consciousness it is spread among all of the voices—the girls, the boys, even some of the adults; though I never lived in Williamsville, I did become close friends with a number of Williamsville girls, and it is these girls’ voices that resound through the dreamily lyric prose.

Ironically, there is a writer in the novel, Evangeline Fesnacht, morbid-minded, graceless, and aggressive, but she is one of the “nobly-born” inner circle, who’d gone to kindergarten in Willowsville—a special enclave of privileged students known as the Circle—”eight girls, five boys, from prominent Willowsville families.”

It is particularly ironic in that, though I am certainly not Evangeline, and Evangeline is certainly not me, it would happen one day that I, too, like Evangeline Fesnacht, would be interviewed at length for a profile in The New Yorker—for me, not until 2023 in another century, and another era, as distant from the sequestered 1950s as if inhabiting another planet.

Names of my Williamsville classmates are threaded through Broke Heart Blues in the way in which stray pieces of yarn, paper, twine are threaded through birds’ nests; names of Williamsville stores and tradespeople, names of parks, buildings, creeks in the vicinity including Buffalo and Niagara Falls, find their way in unexpected passages in the novel.

In rereading, I feel a clutch of the heart, and tears starting in my eyes, on virtually every page: this is indeed a scrapbook of emotionally intense memories, of a time when I was not an adult, not a published writer, but a high school girl staring and listening as if my life depended upon it, not even knowing how I was memorizing this idyllic suburban world in which I did not belong except as a visitor from the north country.

John Reddy Heart and his glamorous, beguiling, cruelly self-centered mother Dahlia are the material of myth, or ballads: beautiful people who exert an otherworld spell. I had wanted to bathe John Reddy Heart in the glow of adolescent infatuation in Part I of the novel, titled “Killer-Boy”; and then, in Part II, titled “Mr. Fix-It,” to de-glamorize him as an adult who has become chastened and broken by life, living now not in affluent Erie County but in an approximation of Niagara County, a place of small fruit farms south of Lake Ontario.

In this incarnation John Reddy resembles my father, Frederic Oates, who’d also hired himself out as a sign painter and was wonderfully “handy” as so many men had to be in that era, if they led frugal lives; you did not hire a handyman, you were a handyman.

Like John Reddy, my father was a highly capable carpenter, painter, repairman. John Reddy even resembles my young father. (“You never knew when you might see John Heart again”—by the time of this writing, my father Frederic had only two more years to live, though no one knew it at the time.)

“Thirtieth Reunion”—Part III—is a giddy rendering of the Willowsville class reunion where, abruptly, the romantic-minded teenagers have become middle-aged, some of them even white-haired, and some of them even deceased.

It’s a vertiginous leap—like such leaps in our own lives—one day you are sixteen, the next you are forty-six; beyond that, if you are fortunate, you are seventy-six, eighty-six; and still trying to discover, as one of the characters says, “if life is truly so random as it’s come to seem in middle age. Or whether there’s a pattern, a design. In which somehow [you] fit.”

Who better than “old buddies and classmates” to help us find it?

Everyone at the reunion awaits John Reddy Heart: will HE return? The novel is, in part, a mystery; a murder mystery; if you read closely enough, you will learn that the murderer at the heart of the novel may not be the person you’d been led to think he is, as the choral voices of Broke Heart Blues may have been deceived as well.

Life itself is the “blues”—life itself breaks our hearts, which is the price we must pay for its beauty and terror.

It is fitting that my novel ends in a lyric passage like a prose poem naming the names of my actual classmates and friends—so many of them, in 2024, now deceased. My appeal to them is forlorn with yearning: Where are you?

But then, it is only what we must expect, and accept. Life itself is the “blues”—life itself breaks our hearts, which is the price we must pay for its beauty and terror.

______________________________

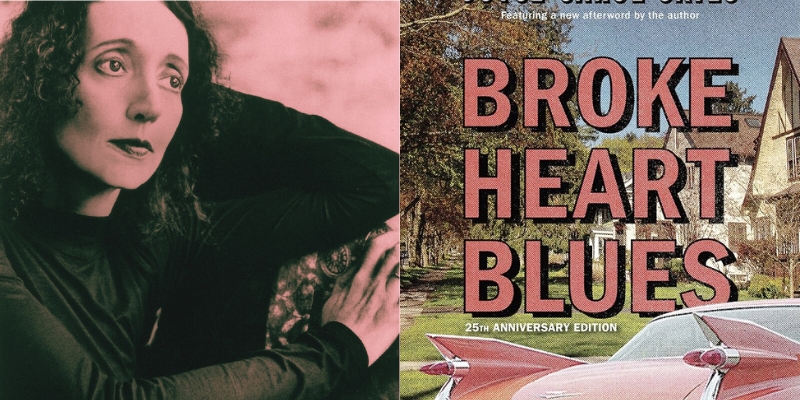

Broke Heart Blues by Joyce Carol Oates is available via Akashic Books.