According to the powers that be (er, apparently according to Dan Wickett of the Emerging Writers Network), May is Short Story Month. To celebrate, for the third year in a row, the Literary Hub staff will be recommending a single short story, free* to read online, every (work) day of the month. Why not read along with us? Today, we recommend:

Isaac Asimov, “Nightfall”

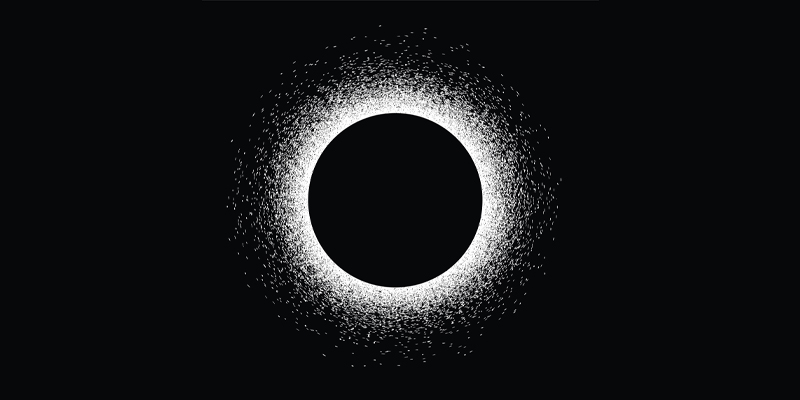

In 1941, just a few weeks into spring, John W. Campbell, the editor of Astounding Science Fiction, read Isaac Asimov—then a little-known writer, with fifteen magazine stories to his name, but none of his present-day fame—a quote that changed his life. “If the stars should appear one night in a thousand years,” Campbell read aloud in a passage from Ralph Waldo Emerson, “how would men believe and adore, and preserve for many generations the remembrance of the city of God!” The idea was simple yet profound: that we see marvels, like the night’s stars, so frequently that we take them for granted, gradually disenchant them; by contrast, if we only saw stars once in many generations, we would view them with the transcendent air of a mystic, the sky filled with a significance as much luminous as numinous.

Campbell, however, disliked Emerson’s optimism. “I think Emerson is wrong,” he told Asimov. “I think that if the stars would appear one night in a thousand years, people would go crazy. I want you to write a story about that and call it ‘Nightfall.’”

At the time, Asimov, as he reveals in his memoir I, Asimov, believed he had as yet “failed to do anything outstanding” as a writer. So he took up Campbell’s challenge and wrote “Nightfall,” a long short story—arguably a novelette—about a society on another planet, Lagash, that experiences a solar eclipse—and true darkness—for the first time. The planet is normally shielded from the dark by its six suns, but every two millennia, its civilizations have inexplicably burnt down to the ground, and the story’s protagonists are at their own version of this point in the disconcerting cycle. A religious group claims a dark apocalypse is here; a few scientists agree that night, virtually unknown to Lagashians, will fall and throw the world into chaos; and most of Lagash is in a state of bemused skepticism, unsure what to believe, but doubting the scientists’ and cultists’ warnings alike. What happens next is a test, indeed, of Emerson’s quote.

“Nightfall” reignited Asimov’s career. (Decades later, it would be adapted into a novel with Robert Silverberg.) While imperfect and dated in its dialogue and depictions of gender—women exist in the story only in passing references about breeding, amongst other things—the story captures an intersection of institutional distrust, uncertainty, religious fanaticism, and apocalyptic unease that feels relevant today—as well as, if more subtly, a reminder to look up at our own more common stars, and take some time to wonder what we, too, might think, were we to see those strange celestial blazes for the first time.

The story begins:

Aton 77, director of Saro University, thrust out a belligerent lower lip and glared at the young newspaperman in a hot fury.

Theremon 762 took that fury in his stride. In his earlier days, when his now widely syndicated column was only a mad idea in a cub reporter’s

mind, he had specialized in ‘impossible’ interviews. It had cost him bruises, black eyes, and broken bones; but it had given him an ample supply of coolness and self-confidence. So he lowered the outthrust hand that had been so pointedly ignored and calmly waited for the aged director to get over the worst. Astronomers were queer ducks, anyway, and if Aton’s actions of the last two months meant anything; this same Aton was the queer-duckiest of the lot.

Aton 77 found his voice, and though it trembled with restrained emotion, the careful, somewhat pedantic phraseology, for which the famous

astronomer was noted, did not abandon him.

Read it here.

*If you hit a paywall, we recommend trying with a different/private/incognito browser (but listen, you didn’t hear it from us).