It feels wrong to describe Saul Steinberg’s work in words; it simply transcends them. Steinberg called himself “a writer who draws,” perhaps because he didn’t have a language of his own: he disowned his native Romanian when he left for Italy at nineteen, and adopted English when he moved to the United States in his late twenties. But his drawings are absolutely fluent in a way drawings rarely are. Or words, for that matter.

In America he re-created himself, and re-created the medium of cartooning: from something parochial—conservatively illustrated one-liners that often aged fast—into something free, proudly individual and endlessly surprising. Jokes were replaced by ideas, elegantly pinned down and illuminated. In an interview with Adam Gopnik, Steinberg said of his earlier gag cartoons:

They were controlled by the censorship of myself as an editor, as somebody who is doing some art for a certain public and has to make it understood, slowly. I progressively made it more and more courageous, breaking certain taboos, especially giving more credit to [readers for their] intelligence, so that certain things that were very stenographic and more like secrets of myself, I made public so that they were received with understanding. Let’s not forget that I took advantage of one element about [The New Yorker], which had to do with snobbishness—so many people pretended to understand it. They wouldn’t admit they don’t….I took advantage of this thing, you hammered it in and slowly it is understood.

So when Steinberg began working for The New Yorker, he drew what he thought his audience could comprehend, and gradually made his drawings more complex and philosophical, bringing his audience along with him.

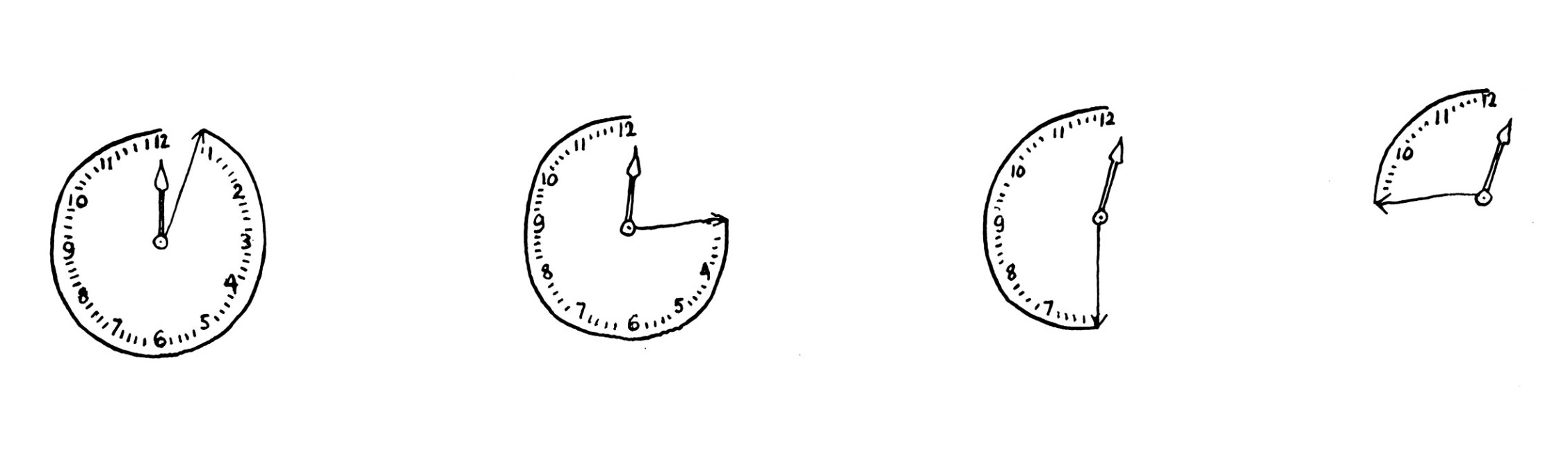

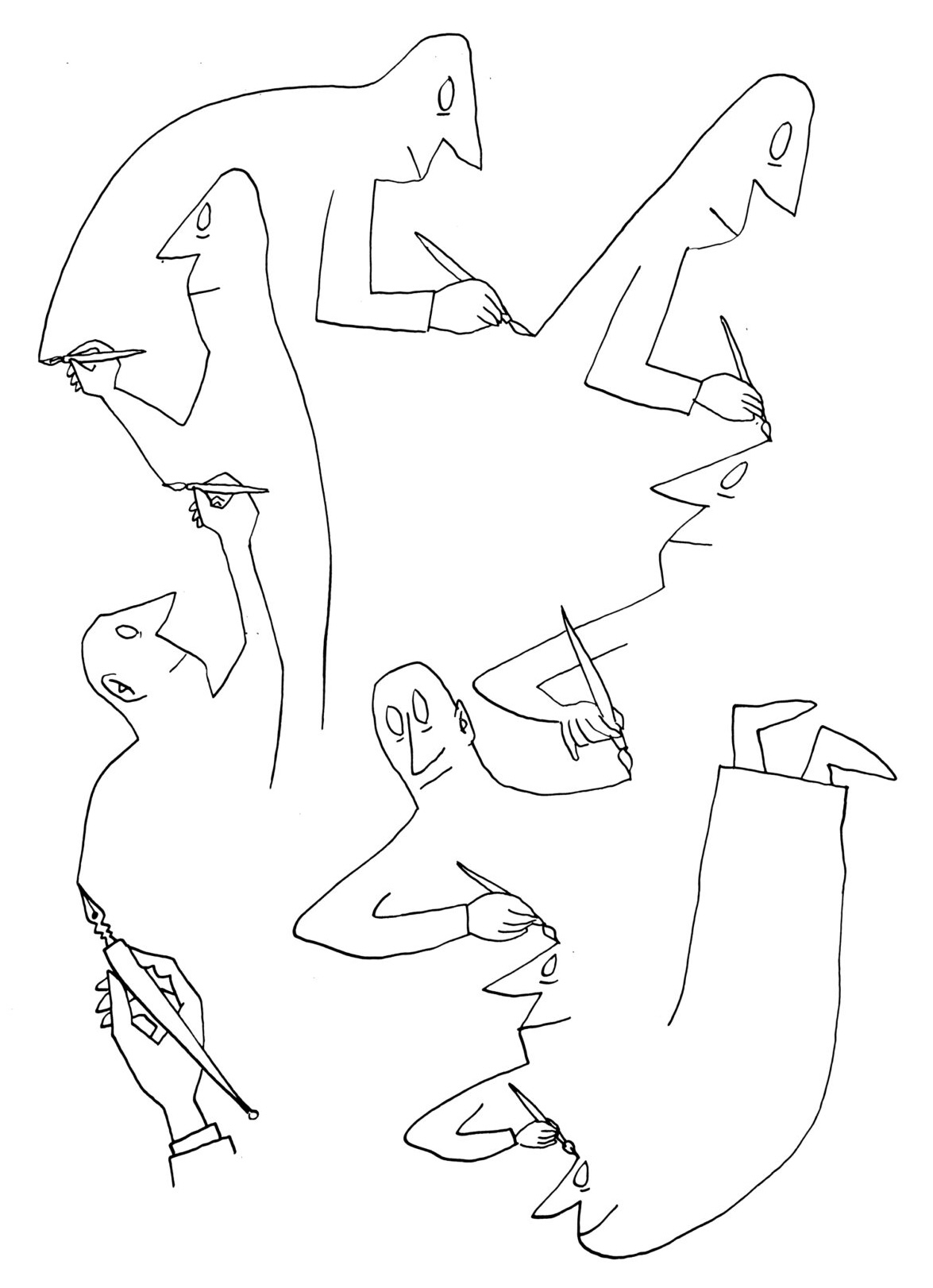

This metamorphosis is the secret drama of Steinberg’s first book, All in Line. Half visual wit and half observational drawings of military life in different US-occupied countries that he made while serving in the Office of Strategic Services during World War II, the collection also serves as a record of his transformation from gag cartoonist to, well, Saul Steinberg—the winking philosopher, the artist of the metaphysical. Here we can see him shift from work that was clever and elegant but still formulaic to something more expansive and completely singular. This is the book in which he cajoled his audience into coming along for the ride, and that made him known. Both pragmatic and ambitious, it includes a few older cartoons Steinberg felt he’d outgrown, and wilder, deeper things, too. He draws abstract concepts and grand mysteries with the same elegant directness he uses to draw anecdotal moments from daily life. His drawings of time vanishing and of an artist drawing himself are as disarmingly concrete as the one of a group of men tilting their heads to read newspaper headlines at a newsstand.

Steinberg is a good artist crush. In photographs he sometimes wore a mask, a paper bag with a self-portrait drawn on it, which any cartoonist knows is more relatable than a face. (Faces are multi-dimensional and ever-changing. Compared with a nice, simple paper-bag drawing, they are like vapor.) His drawings have a feeling of inevitability, too—better than anything one could have come up with oneself, but still somehow so familiar that they feel as if one would have come up with them oneself. He used a range of techniques with deceptive ease: calligraphy, watercolor, rubber stamps, colored pencil, collage, the French curve ruler and other tracing tools.

He drew in order to think, not the other way around, and he brings the viewer into his thought process.

In architecture school in Milan he had learned to draw—and possibly also to think—in perspective. But he carried his techniques lightly: he used them as tools rather than as ends in themselves. If you try to imitate his style, you’ll fall into the trap of obsessing over how to get the right line out of a steel-nib pen or how exactly to draw a row of tall buildings receding into the distance, and miss the point. His perfect ease can’t be faked.

He drew in order to think, not the other way around, and he brings the viewer into his thought process, letting us see the hesitations, the small wiggles in his line. His line is charmingly candid—vulnerable Matisse rather than suave Ingres. He lets us see when he falters, just a little, because he knows he will never fall.

In her book Visual Thinking, the author Temple Grandin suggests that there are two ways of thinking in pictures: there are the thought-pictures that look like detailed photographs or films, and those that come to us in clear, simple symbols. Steinberg began as a cartoonist for humor newspapers during his student years in Milan, where he realized that cartooning, unlike painting or drawing or film, is an art of thinking in straight-to-the-point symbols—a perception that he brought to America and then transformed into a different kind of graphic expression.

I think all the drawings in All In Line—the dated gag cartoons poking fun at lady artists, the slice-of-life war drawing of a soldier with his feet up on a conquered Italian chair, and the pure idea drawing of the clock eating itself—are all of a piece. Steinberg was making sense of, and making concrete, the ideas around him. This might be why All in Line, like the rest of Steinberg’s work, still feels so alive today. Some ideas change—but Steinberg’s ability to visualize them endures and continues to surprise.

I used to wish I’d known Saul Steinberg. He was always my answer to the “if you could have dinner with anybody” question. But I now wonder if that would have gotten in the way of knowing the real Steinberg. Dinner is for friends. You can never see your idols face-to-face, only in profile. For me, the real Steinberg exists only—and all—in line.

__________________________________

From All in Line by Saul Steinberg. Introduction by Liana Finck. Copyright © 2024. Available from New York Review Books.