As the summer begins to wane, cases of mosquito-borne diseases are creeping up in some parts of the United States. In other regions, the threat of malaria is a more constant issue even as vaccines continue to roll out. However, some new research on how they mate may help develop better improved techniques for controlling the mosquitoes that carry malaria.

For male mosquitoes–who do not bite–the high-pitched buzzing of females is siren call that signals it is time to mate. However, there is even more to that signal than scientists first realized. When a male Anopheles coluzzii mosquito picks up the sound of female-specific wingbeats, his vision becomes active. These findings are detailed in a study published August 30 in the journal Current Biology.

Finding weak spots

Mosquitoes are the deadliest animal on Earth, spreading diseases including Dengue fever, West Nile virus, and eastern equine encephalitis (EEE). The World Health Organization estimates bites from infected mosquitoes cause 219 million cases globally and over 400,000 deaths every year.

Despite being such a dangerous animal, these insects do have weak spots. Many mosquito species have poor vision, including Anopheles coluzzii. This species is a major spreader of malaria in Africa, along with Anopheles stephensi.

[Related: Mosquitoes can sense our body heat.]

In this new study, a team of researchers found that when a male hears the buzz of female mosquito flight, his eyes will “activate.” He then visually scans for a potential mate nearby. Even though A. coluzzii typically mates in busy and crowded swarms, the male can still visually spot his target. He then speeds up his flight and deftly zooms through the swarm, while avoiding collision with others.

“We have discovered this incredibly strong association in male mosquitoes when they are seeking out a mate: They hear the sound of wingbeats at a specific frequency—the kind that females make–and that stimulus engages the visual system,” study co-author and University of Washington biologist Saumya Gupta said in a statement. “It shows the complex interplay at work between different mosquito sensory systems.”

With this new understanding of how well their sensory system picks up the sounds and sights of mates, scientists could develop a new generation of traps specific to the Anopheles mosquitoes that spread malaria.

“This sound is so attractive to males that it causes them to steer toward what they think might be the source, be it an actual female or, perhaps, a mosquito trap,” study co-author and UW biologist Jeffrey Riffell said in a statement.

A mosquito flight simulator

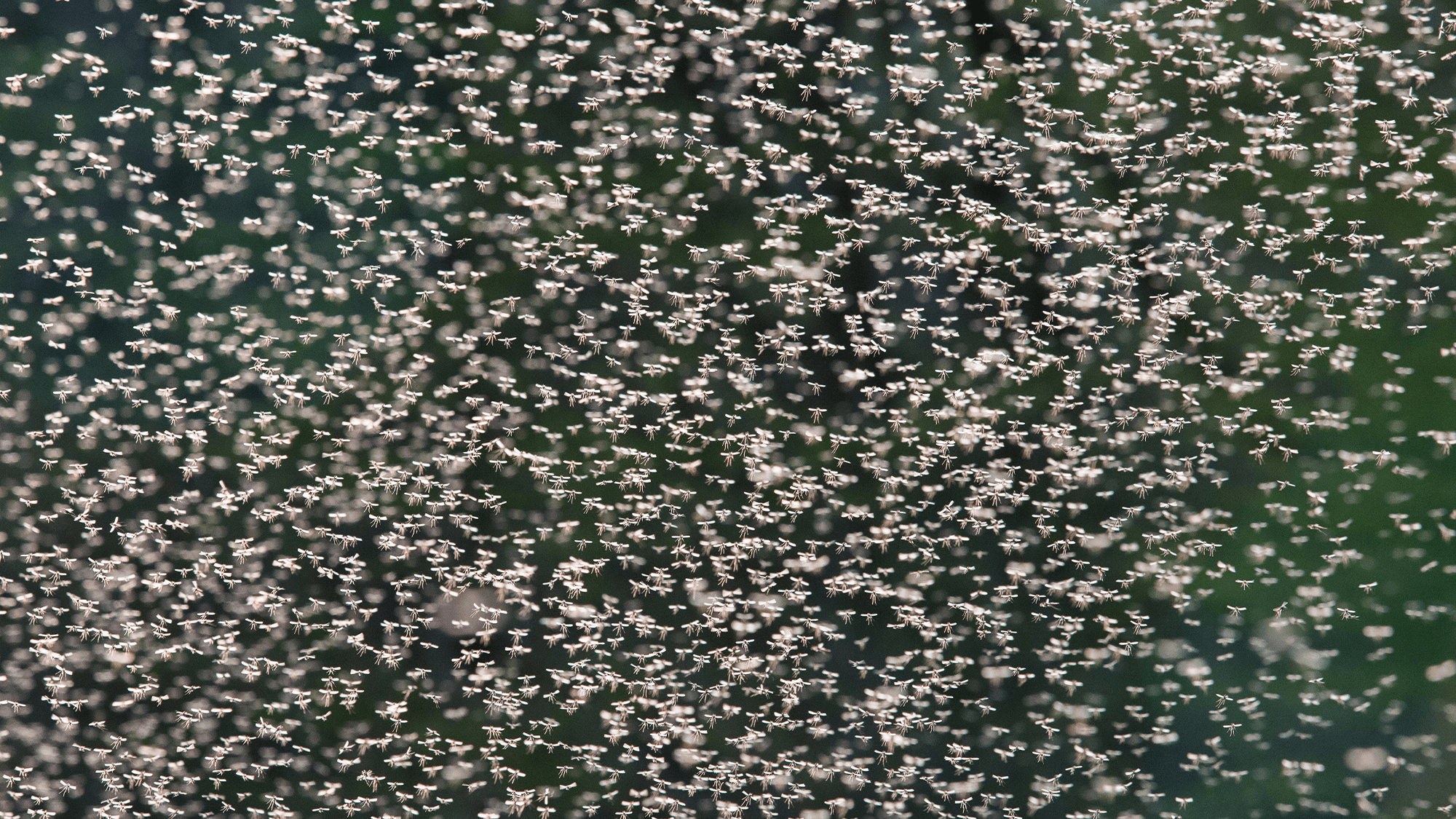

Several Anopheles species mate in large swarms at sunset. The majority of the bugs in these swarms are males, with only a few females. To avoid collisions and find a mate, males must use all of their senses.

To better understand how male mosquito senses work together in these chaotic swarms, the University of Washington team worked with scientists from Wageningen University in the Netherlands, the Health Sciences Research Institute in Burkina Faso, and the University of Montpelier in France.

The team built a miniature arena that uses a curved and pixelated screen to mimic the visual maelstrom happening in a swarm to test how individual male mosquitoes fly. According to the team, the arena was essentially a mosquito flight simulator. The mosquito was tethered and could not freely move, but could still see, smell, and hear, while beating its wings as if it was flying. They conducted tests with dozens of male Anopheles coluzzii mosquitoes.

They discovered that the males responded differently to an object in their field of vision based on which sound was played in the arena. When a tone at the frequency at which female mosquito wings beat in these swarms (450 hertz) was played, the males steered toward the object. When the team played a tone at frequency at which fellow males beat their wings (700 hertz), the male mosquitoes did not try to turn towards the object.

Additionally, the mosquito’s perceived distance to the object also mattered. If a simulated object appeared to be over three body lengths away, he would not turn toward it, even if there were female-like flight tones playing.

“The resolving power of the mosquito eye is about 1,000-fold less than the resolving power of the human eye,” said Riffell. “Mosquitoes tend to use vision for more passive behaviors, like avoiding other objects and controlling their position.”

The arena experiments also revealed that males made a different set of subtle flight adjustments. They changed their wingbeat amplitude and frequency in response to an object in their field of vision, even if there weren’t any audible wingbeat sounds. The team hypothesized that visually driven responses could be a set of preparatory maneuvers in order to avoid an object. To test it, they filmed male-only swarms in the lab. The analyses of those movements showed that males moved away when they got close to another male.

“We believe our results indicate that males use close-range visual cues for collision avoidance within swarms,” said Gupta. “However, hearing female flight tones appears to dramatically alter their behavior, suggesting the importance of integrating sound and visual information.”

New traps with sound?

According to the team, this research could demonstrate a new method for mosquito control that works by targeting how mosquitoes integrate auditory and visual cues. The strong and consistent attraction to visual cues when a male hears a female buzz could be a weak spot that researchers can use when designing new mosquito traps.

[Related: How can we control mosquitos? Deactivate their sperm.]

“Mosquito swarms are a popular target for mosquito control efforts, because it really leads to a strong reduction in biting overall,” said Riffell. “But today’s measures, like insecticides, are increasingly less effective as mosquitoes evolve resistance. We need new approaches, like lures or traps, which will draw in mosquitoes with high fidelity.”